Reimagining folk horror – Licorice and the legend of Nan Kemp

Nan Kemp’s Corner near Lewes in Sussex, said to be the burial place of local woman Nan Kemp who, in 18th Century, was said to have killed her illegitimate child and fed him in a pie to her husband. The story has many versions, which are the subject of the film being made by the protagonist in Bridget Penney’s novel Licorice, currently our Book of The Month.

A now-nearly-illegible sign reading “Nan Kemp’s Corner” is all that remains to mark the site of this grisly Sussex legend of infanticide, cannibalism and rough justice . In the 17th and into the 18th centuries, people who died by suicide were usually buried at a crossroads (often, some histories tell us, with a stake driven through their heart, though it’s unclear that this was common practice in reality). The legend of Nan Kemp has it that she murdered her newborn baby, baked it into a pie and fed the pie to her husband, although local historians say the real story was a more prosaic and tragic one. The legend was likely embellished from the fact that she hid the baby’s body in the oven before committing suicide.

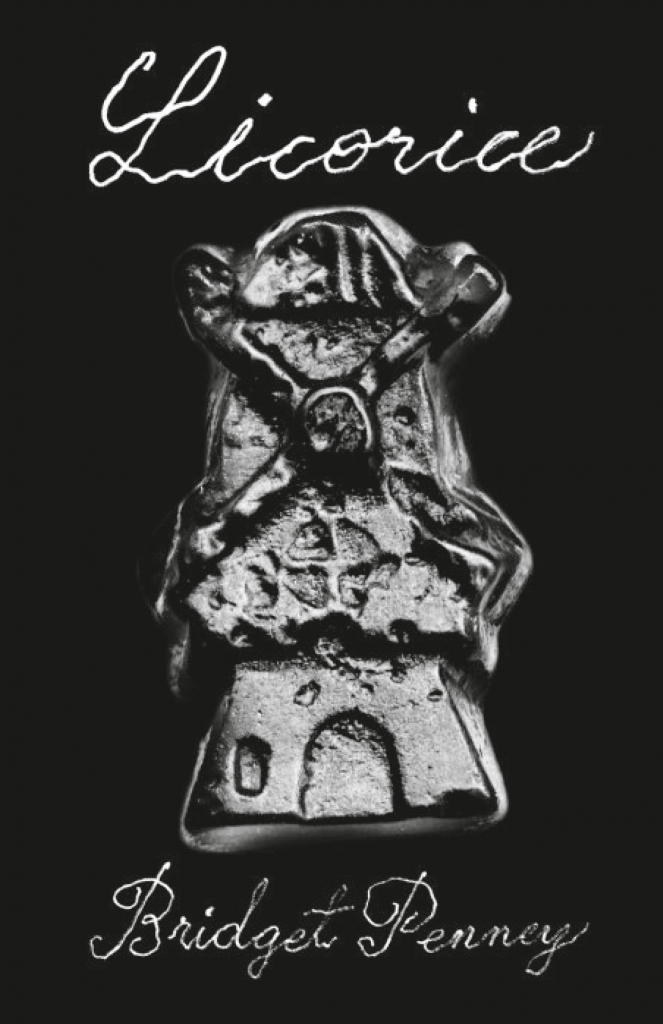

Licorice draws on and upends folk horror tropes the story of an ill-fated film production based on the story of Nan Kemp. As the shoot descends into chaos, both the text and its protagonists grow increasingly tense and uneasy. See below for some review quotes, and order Licorice before midnight on 30 November for a 30% discount.

Folk horror has always been plagued by the two-dimensional depiction of the very ‘folk’ in which it locates its threat, its agrarian mobs and peasant hordes nothing more than a pulsating backdrop of undifferentiated ciphers evoking a deeply English fear of class antagonism. Often reading like a lost Mike Leigh script re-penned with the deft conversational dynamism of American novelist Barry Gifford, Licorice brilliantly foregrounds and realises its own folk through chaotic streams of both spoken and internal dialogue, inter-generational and trans-cultural frictions, its characters haunted by a tale as apocryphal as the very Englishness within which it is steeped.

Jamie Sutcliffe, Art Monthly

A tension is afoot between English folk horror – an inherently conservative genre, with its moralizing bent and nationalist overtones – and the avant-garde. Penney sparks the two off against each other to achieve a fertile kind of “brinkmanship”. It takes an outsider, such as Licorice, to assert, “Fuck authenticity I say now it is the ultimate illusion, a distancing mechanism to maintain the fourth wall as the magic circle which cannot be crossed”. Licorice crosses these boundaries with swift grace.

Anna Aslanyan, Times Literary Supplement

Images:

top: the sign is now worn and difficult to decipher, but Patrick Davies uploaded this photo, taken in 1981, to their Flickr account.

bottom: a more recent image of the crossroads at which Nan was thought to have been buried, also from Flickr.