Blog post 2: shame requires an audience by Sophie Collins

In the literature on shame I expected there to be competing definitions. In reality, most of the texts were tautological, both as a group and in and of themselves.…Wisdom proffers a distinction between shame and guilt that posits the latter as a uniquely private and inwardly felt emotion, and the former as dependent on external public judgement, or anticipation thereof. In Pride, Shame and Guilt, Gabriele Taylor writes that ‘shame requires an audience’…

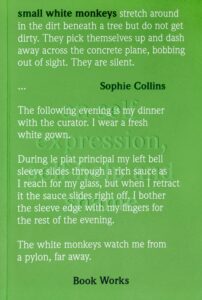

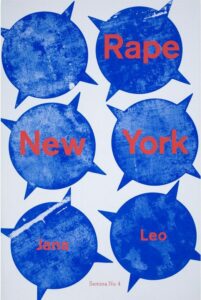

– small white monkeys 1

For me, shame has been the product of changing perceptions (aesthetic-intellectual-cultural-political), of feeling exposed and inadequate (when it comes to writing, publishing and reading my work to others) and of having been sexually assaulted. I note that I did not feel a strong sense of shame in childhood or adolescence, as I’ve heard others attest to. For me, shame is a condition of adulthood – a new and burgeoning state.

A couple of years ago I began seeing a psychotherapist through Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre to help with some of the shame. Towards the end of my six-month course, me and my therapist Sara spoke about what I might do next to continue with my process of recovery and integration. We’d spoken a lot about writing and my work in poetry. We thought I might write a book.

As this origin story suggests, small white monkeys focuses – though not exclusively – on the shame engendered by sexual assault. The text takes as its starting point a poem I didn’t know I could write and the image of the white monkeys at the poem’s centre – literally, in terms of its positioning in ‘The Engine’, but in a more intangible sense also; friends and strangers would often comment on that particular part of the poem after hearing or reading it. This is something I remark on in the book:

Shortly after she had heard me read ‘The Engine’ aloud at a literary event, a friend of mine reported having seen two white monkeys scrabbling about on a factory roof in industrial Glasgow. Though of course it was a hallucination, she quickly added – as she got closer to the building, it became obvious that the white monkeys were in fact two large white cats. But what was strange, she said, was that both animals had somehow been left with stumps for tails. Another friend recently sent me, via text, an image of an African tapestry in which a monkey is trying to tear a cloth covering from a woman’s head, prizing it away with one monkey hand, its two monkey feet planted on her hunched shoulders for leverage.

small white monkeys is thus a commentary on a poem, a personal account of shame and a record of research, among other things (including, I might add, a homage to cats and their powers). Two things that felt pivotal to developing my own understanding of shame, and that I grapple with in the book, are the common conception of shame as dependent on public or external judgement (something that I see as being complicated by the belief in and/or presence of a non-essential self) and shame’s relationship to writing, poetry and self-expression. The latter is something that I know we will work through today.

I have told you a bit about my own shame, but the sources of shame are of course far more diverse than those named above – they are, in fact, innumerable. Of particular interest to me are the forms of shame expressed by those who I have invited to speak at this event. In a recent interview, Emily Berry wrote about death and blushing (the latter being our immediate and physiological response to shame):

I guess there must be some kind of connection between embarrassment and death – I mean, to be ‘mortified’ literally means to be put to death. Personally, I felt huge embarrassment about my mother’s death when I was a child. She died when I was seven – it’s rare for kids to have a dead mother; when you’re a child, your parents are mentioned constantly, and I found it so embarrassing to have to explain every time. We’re still embarrassed as adults, because our particular culture hasn’t developed very sophisticated ways of responding to it – the language is very limited. Perhaps it’s also something to do with the way that death – and suicide especially – implicates the living. It reminds us of our own mortality, which is embarrassing, because everything to do with the body is embarrassing, and it shows us how thoroughly we have failed to keep another member of our species alive. 2

In Emily’s work, then, and in the work of Wayne Holloway-Smith and Holly Pester, childhood is a site of shame, even if retroactively. In their writing, and in the other texts in this pamphlet by Vahni Capildeo, Aniela Piasecka and Nuar Alsadir, death, parents, family, illness, the self, violence and assault are all broken open as shameful sources.

Key to keeping people alive is alleviating their shame. One way in which shame can be alleviated is through self-actualisation. Glasgow Women’s Library is the only accredited museum in the UK dedicated to women’s lives, achievements and histories. The library’s archives include the Scottish Women’s Aid archives, the Women’s Suffrage Collection and the Scottish and National Abortion Campaign archives, as well as archives of artists’ work, including the Dorothy Dick and Hannah Frank collections. The library has helped me and countless other women recognise themselves. It was the perfect place to write small white monkeys and is the perfect place to be speaking today.

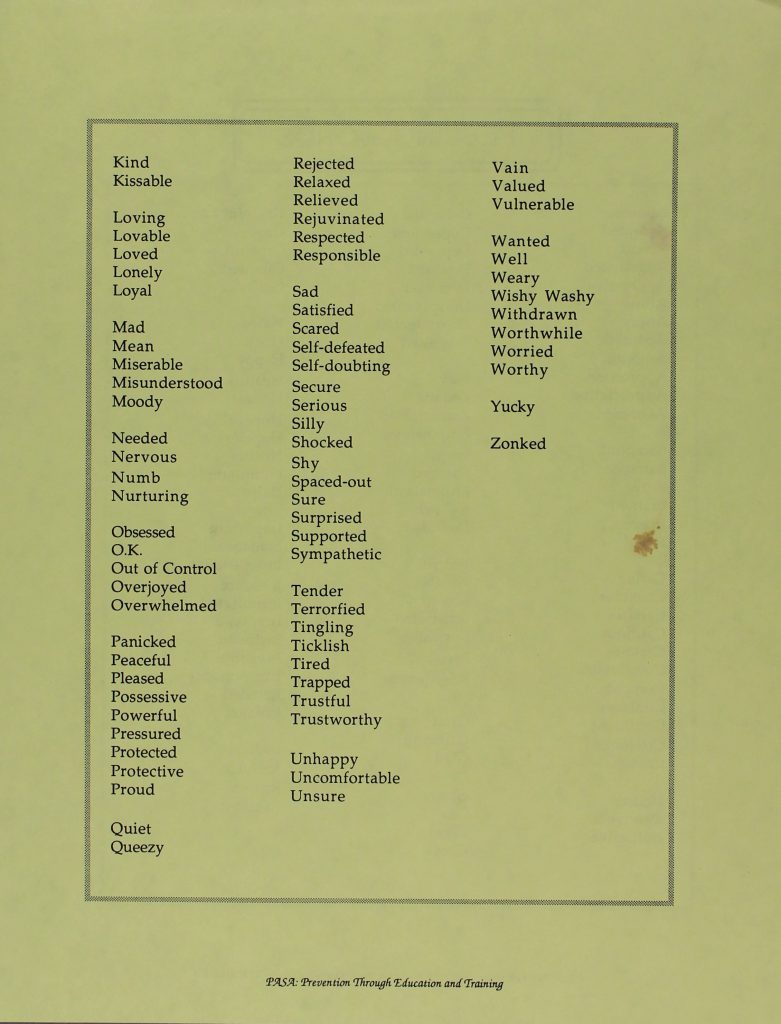

The essay(s) and poems in small white monkeys were made through research into Glasgow Women’s Library’s materials and resources, and with the help of the library’s staff and the library’s atmosphere of support. I started in the Violence Against Women archives, which include records from the Edinburgh and Glasgow Rape Crisis Centres, and the Zero Tolerance archives. I began my research by compiling a document of first-person accounts and testimonies pertaining to experiences of sexual violence and associated trauma. The result was something akin to Svetlana Alexievich’s polyphonic historical writings (as in The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II) and, although it remains unpublished, the voices gathered in this document helped me to find my own. Some of the poems in the book contain fragments or derive their structures from treated archive material, including public information sheets and pamphlets. Much of the writing of small white monkeys took place in the Glasgow Women’s Library, both in the Lending Library, where I was helped by the extensive collection of books by, for and about women (particularly the self-help texts and Women’s Press books), and on the mezzanine level, where archive materials can be accessed.

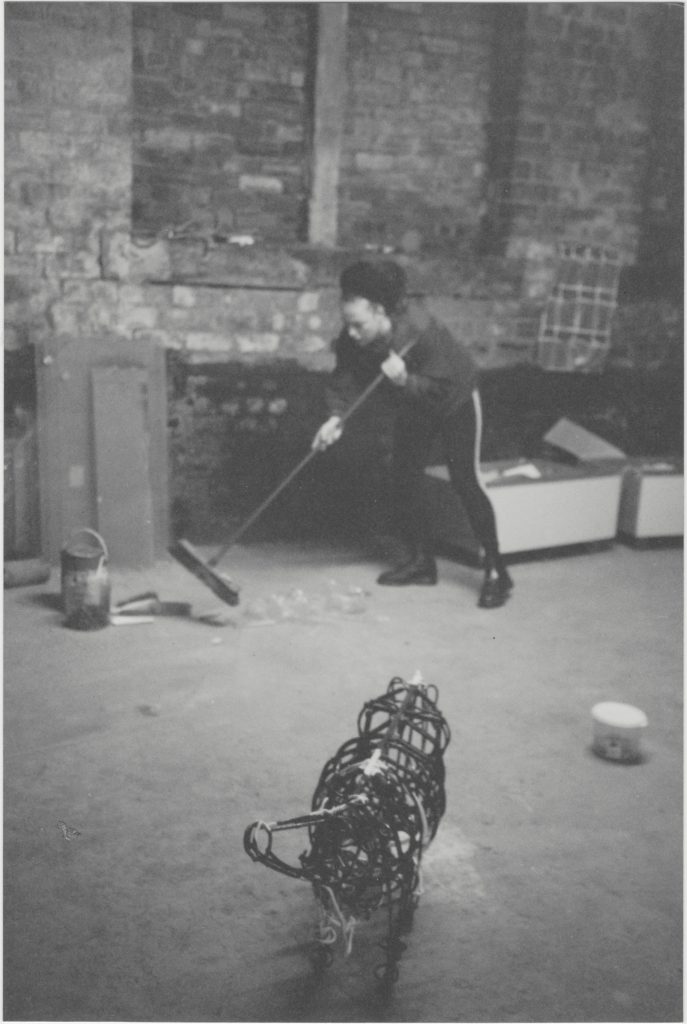

Our event will take place in the library’s Main Events Space, formerly the ‘Gentlemen’s Reading Room’, a men-only room previously populated by large wooden desks that were fixed firmly to the floor. When the Women’s Library got into their new premises on Landressy Street, in 2013, they tore each of these desks up from the root.

For more information about small white monkeys – A day of talks, readings and performances on shame and self-expression, or to book a place please visit the Glasgow Women’s Library booking page here: http://womenslibrary.org.uk/event/small-white-monkeys/