EVENT

Graphic Negotiations – Marwan Kaabour – video and transcript

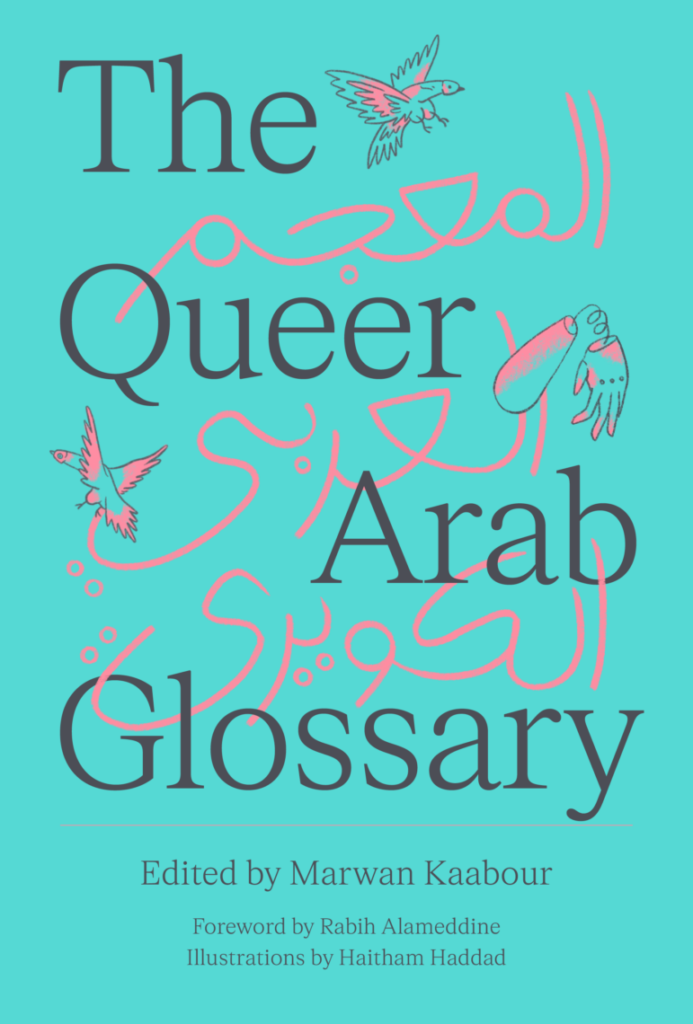

As part of our series of conversations with designers, Graphic Negotiations, we were delighted to welcome graphic designer, artist, founder of Takweer and author of The Queer Arab Glossary, Marwan Kaabour for a chat on Zoom. Below is a full verbatim transcript. If you would like a plain-text version compatible with screen readers, please drop us a message here.

TAMAR SHLAIM (TS) – Hi everyone, thank you for joining. Can everyone hear us okay, for starters? And see us okay?

You can do a thumbs up react or write in the chat.

Cool. Thanks,

Great.

So welcome to— This is the first episode of a second series of this series, which is called Graphic Negotiations. I’m Tamar Shlaim from Book Works and today we have Marwan Kaabour with us.

So I’ll just say a little bit about us and Marwan and this series. We obviously work with designers a lot as a publisher of artists books. And we like to think that we kind of work with designers in an involved and holistic way compared to maybe some other publishers, and design is a very central part of our practice as a publisher. So these events are an opportunity just to talk to some of the designers we work with; find out about their other practice; find out about their thoughts on making artists books, designing artists books.

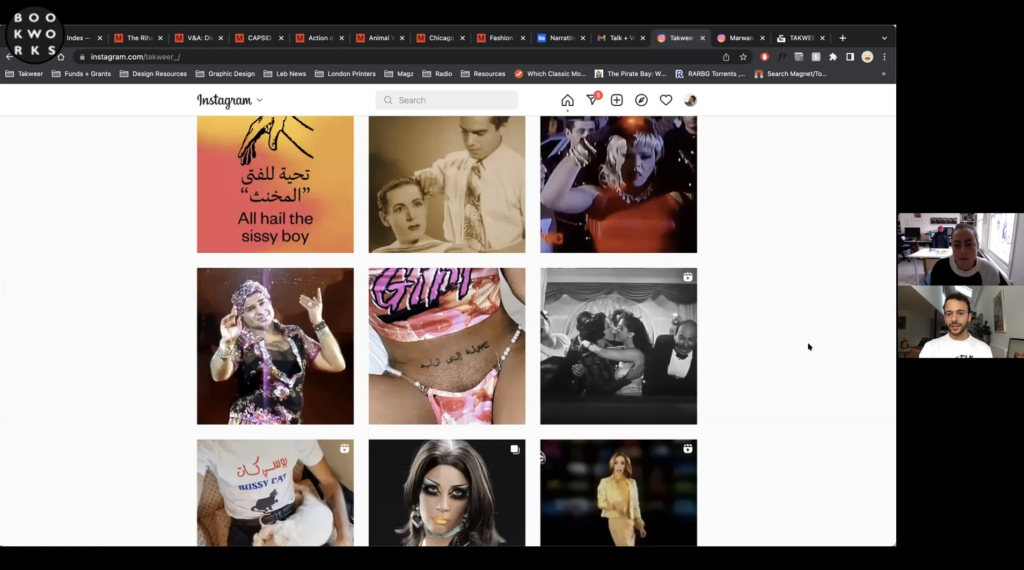

So yeah, we’re really happy to have Marwan Kaabour with us today. Marwan is the founder of Takweer, which is an Instagram account, which sort of documents queer Arab culture. Is that accurate? (01:49)

MARWAN KAABOUR (MK) – Yeah, it attempts to create an — it aims to create a queer reading of Arab history and pop culture.

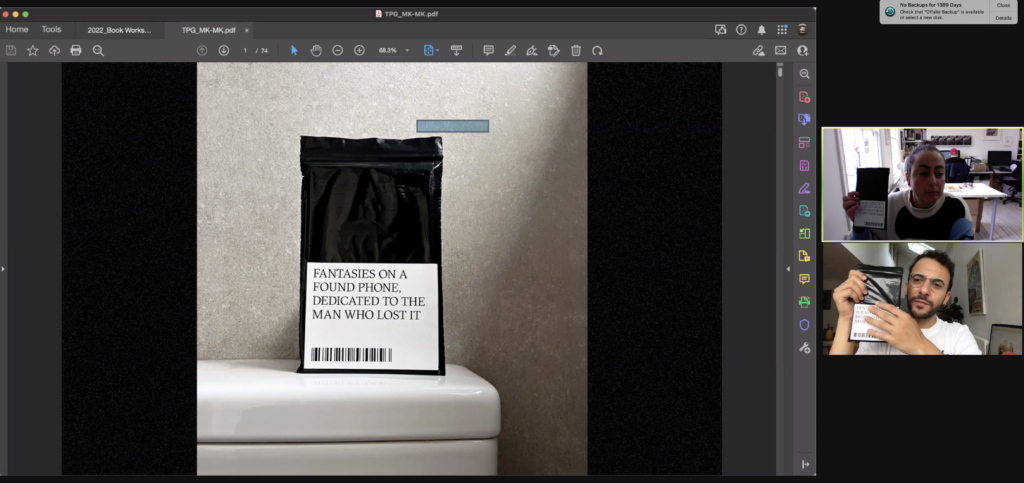

TS – Yeah that’s clearer. Marwan’s worked previously for Barnbrook design agency, but left and set up his own practice in 2020. And is working on his own book as well. We have just worked together on this book, Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost It by Mahmoud Khaled. That’s been in collaboration with the Mosaic Rooms where Mahmoud also had a solo show as part of the same project. So this little book is kind of— won’t say a companion to the show, because it’s not really a companion. It’s part of the same project. Anyway, we’re going to be talking a little bit more about that and about Marwan’s practice in general. Yeah, do you want to..? (02:59)

MK – Yes, sure. Hi, everybody. Thank you for joining us. As Tamar mentioned, my name is Marwan Kaabour. I am a graphic designer. I’m currently based in London. I have been practising graphic design, I don’t know for almost like 15 years now. And bookmaking and book design has been quite a large chunk of my practice. As mentioned before, between 2012 and beginning of 2020, I used to work at Barnbrook, which is Jonathan Barnbrook’s graphic design agency, which is also based here in London, which is really where I kind of begun getting into book design quite seriously. I had done only one book prior to that, but as a studio that prides itself in working a lot with print and publications, it was an exciting space for me to be able to engage with bookmaking as a practice. Since I’ve left, that has taken up even a larger percentage of what I do. In the last two years, I’ve created around, or developed and designed around five or six books. Also as mentioned, I’m currently working on my own one now. (04:27)

So, in regards to my collaboration with Book Works. Mahmoud Khaled who is an Egyptian artist based in Berlin, had his first solo show at the Mosaic Rooms, which actually just closed a few days ago— a couple of days ago. And the exhibition was called Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost It. The premise of this exhibition was that a phone was found in a public bathroom, it was unlocked, and the contents of the phone were revealed. Based on those contents, Mahmoud imagined the spaces that this person occupied. He created a house museum dedicated to this man, based on the findings, or the photos and the gallery. You know, as you can imagine, this is a highly private space for all of us. It says probably more about us than anyone can imagine. So as a companion piece, or a piece of art on its own Mahmoud wanted to well— Just to kind of backtrack a bit, Mahmoud did not want to exhibit these images. These images needed to live on their own, and not as an installation. So he came up with this idea that we should create a publication, an artists book where the—

TS – …a physical representation of the phone.

MK – Exactly. Where we would kind of reveal the findings of the phone. So what happened is, I met Mahmoud, and he told me about the show. He’s been interested in working with me for a while, I’ve been interested in his practice for quite some time. From the very beginning…maybe I should actually…wait, let me share my screen. One second.

From the beginning, there was a shared interest in each other’s practices, which it’s important to mention as it’s really the bedrock of a very successful collaboration in the sense because as you can imagine, artists and creatives are people with quite a lot of ego. And when it comes to sharing work, we kind of all want to take authorship of the work. And we want to take creative authorship. So, in this sense, because of this shared love, interest, curiosity and respect to each other’s practices, it was this seamless project where he gave me around like 400 or 500 images, and the idea was, we need to create a book out of them. An artists book. The book has no text, it’s simply a series of images. But it’s meant to tell the story of this person. So how do you by not seeing a single word tell the story of this person? Just to begin with the object itself. The object comes in— the book, the publication comes in this opaque plastic bag that somehow mimics the proportions of a smartphone– it’s a bit shiny, like the screen of a smartphone as well. Also, it’s discrete, which as you can see is what you want the contents of your photo album on your phone to be, and it kind of mirrors the way adult magazines used to be censored or displayed in magazines shops. (08:49)

TS – We should actually leave some around in strange places for people to find.

MK – Yeah, exactly! Also, one thing to mention about Mahmoud’s practice is he deals a lot with queer men and queer identities and the idea of something a bit leathery, a bit latex–y…something that kind of speaks to the queer collective consciousness somehow. And then inside you literally have to go through quite some effort to reveal the findings of this bag, and then out of it comes these tiny books. Even the cover has barely anything on it. The cover is almost like a silhouette of a man, and here’s where the story begins to be told. It begins to question the identity of this person. The idea here is to cause intrigue and to maintain a level of mystery. This is what a book cover is meant to do. Yes, it could announce the title, the artist, but the most important thing is… What is the first line of this act? What is the first line in the song? And it’s this which is a silhouetted man behind some kind of veil. And then what went on— Can you see my screen that I’m sharing?

TS – Yeah.

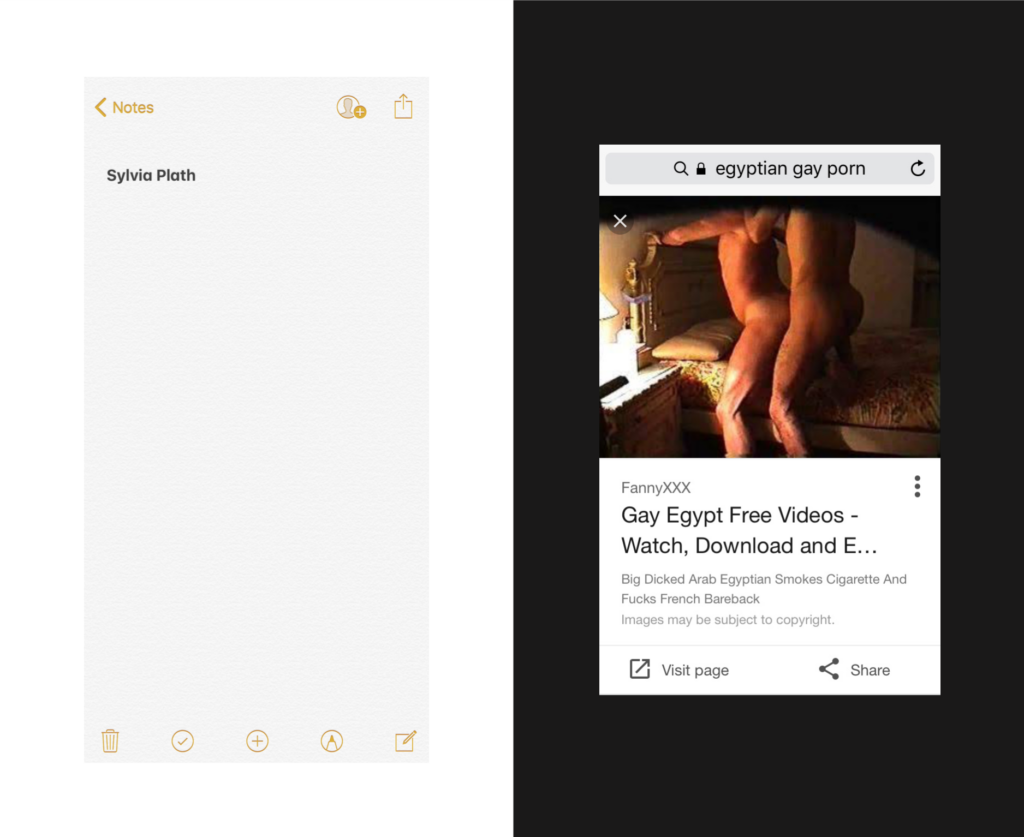

MK – Okay, yeah. Then inside is this just endless stream of images. It’s a mix of screenshots from a phone, images that might or might not be connected, like you would scroll through your gallery… you get these interesting, unexpected juxtapositions. Sometimes they’re funny, sometimes they’re a bit humorous, they’re dark. Sometimes they’re repetitive, you know, you take 16 selfies just to choose the right one, or you see something and you’re trying to take a picture of it until you get it right. And this feeling of accidental juxtapositions is what we tried to emulate in the layout of this book. So just to kind of show you, it’s kind of similar as we’re seeing on the screen, and it’s just this kind of endless stream of it.

TS – And it’s not just photos it’s also screenshots, texts, notes…chats…

MK – Yeah, because I mean, just think of your phone. When you scroll through it, it’s gonna be this barrage of random material, some of it is images you’ve taken, or this meme you just saw, and you decided to take a screenshot, you must have written something in the Notes app that you wanted to remember…

TS – This is my favourite, which maybe you’ve got an actual screenshot of…

MK – Oh, of course

TS – This is my favourite spread in all the book.

MK – This also got me banned from Instagram, so there’s a story there.

TS – Also the note is so relatable, like, I always leave myself notes that are just like a word, and then I’m like ”what about it though?”

MK – Yeah, yeah exactly.

The idea is to tell the story of this man. Who is this man? What is he interested in? What are the spaces that he occupies? And then to try and just give a little bit of sense about who he is as a person. Is he funny? Is he intelligent? Is he vague? Is he insecure? And these are the things that we try to do through this book. So clearly, this is someone who has a lot of interest in history, and art and interiors. There’s a lot of interior shots. There’s a lot of like, sites that this person has visited, of two kinds. Like, here we can see an antique shop, juxtaposed with an image of what seems to be someone’s sweat marks left on the bed. And then there’s this parallelism created between the two. Here again, it’s a screenshot plus what seems to be an image taken from perhaps, I believe, is prisoners being tortured in Egypt.

TS – Sorry, are you sharing slides?

MK – Yeah.

TS – Oh, no, we’ve just got a static image. Sorry.

MK – Oh, that’s strange. Um, oh!

TS – There we go.

MK – Oh, sorry. Yeah. Oh, when I put it on full screen…

So clearly, this man is interested in history and interiors; there’s a lot of images of these very Baroque, very over the top interiors. There’s also a lot of images of him being reflected in mirrors or reflective surfaces. So again, there’s this idea of documenting oneself. So we could tell he’s a man, we could kind of vaguely guess his age, or his ethnicity, or his background, so it gives us clues. There’s lots of images of empty beds, empty beds that have once been occupied, which can either allude to a sense of loneliness or anxiety or restlessness. Or, as you can see here, the marks left on a bed. Then all of a sudden we get an image like on the right here, it’s an image of prisoners being tortured in Egypt. I mean, obviously, you might not know the context of this image— (14:44)

TS – I was gonna say, do you want to say a little bit about the context in the photo?

MK – Yes. So to be frank, I don’t know exactly the context of this individual, but Egyptian prisons are notorious for having a lot of abuse and torture towards prisoners. Particularly towards those who have been arrested on the assumption of partaking in homosexual acts. Mahmoud has previously worked on this subject by dedicating one of his shows to the Crying Man, which is an image of this man who was arrested as part of a raid on a gay party, essentially, where 52 men were arrested, and then dragged through the media and humiliated and put in prison. So I think, again, to go back to the book, you kind of understand that this man is interested in other men as well, and perhaps the histories of these people. Here we see the leftovers of what seems to be a cruising area. So again, we’re trying to kind of build this character as we go on. And then all of a sudden, from the cruising area, he’s at some tourist site, which is, again, similar to how we operate in life to kind of traverse different spaces in different times. He’s interested in maintaining some kind of fitness, and then again, empty beds, empty spaces…

TS – There’s definitely a sense of exile. And I guess like…yeah, sort of alienation and exile… on multiple levels, I guess, really, because there’s a sort of queer exile and political exile and being part of, you know, various diasporas… Yeah, I don’t feel that you need to know that backstory to get—

MK – no, no, no,

TS – but it does add a sort of…

MK – Of course. Yeah, it’s to give hints. The rest is left up for the imagination of the reader, they can decide who this person is, we are not trying to tell them. We’re just trying to give them visual cues in the form of one image next to the other, which might make them curious or laugh, they can chuckle or maybe feel a bit like, “Oh, that’s a bit odd.” This is the kind of emotional journey we’re trying to create in this book. Yeah?

TS – I was just going to say, like, when you were in conversation with Mahmoud the other day, you were talking about the sort of…Well, you were saying before, it was a collaboration that really worked. And like, it just seems like you both got exactly what the character was, what the story was you were trying to tell. We call this ‘Graphic Negotiations’ because it’s often, you know, quite a tough negotiation between…when you’ve got designers who are…you know, we don’t hire a designer to design a cover. The designer’s involved from the beginning and that can be fraught, like you said. You both have ideas, you know, you both have ideas of how it should look, etc. But it seems like in this case, it was just like, a kind of…convergence (18:23)

MK – For sure. I mean, I’ve had many clients in the past where the visions clash, or they don’t align at all, and you still need to do the job. So it ends up with a discussion, a compromise, sometimes it’s less pleasant. Sometimes there’s actual tension and that tension carries through into the making of the book and the production of the book, or any kind of project, basically. But in this case, I’ve been really fortunate because it was almost completely frictionless. And I think it’s not a coincidence, as two creatives coming from the Arab region, who identify as queer, we understand what these stories are. I understand what the nuances that Mahmoud was trying to include in this book. So there was no… we let go of that level of having to justify or explain ourselves, which we find ourselves most of the time in a position where we have to kind of explain. I think a European queer person or someone who grew up here – and this could be someone who is a person of colour or a white person– because you exist in the West, your culture is the dominant culture. Your culture is the one being disseminated. It’s your memes that we are consuming. It is your films, your cinema, your music that the rest of the world is consuming. While our perspectives are slightly less, not slightly, significantly less visible. So, most of the time we find ourselves in a space where we have to give context and provide nuance and all of these things, which is, you know, like some people find it…We deal with it in different ways. In this case, we were both at an equal playing field. It was really exciting because there was no— we did not need to do the explanation. We just jumped straight in.

TS – Jumped straight to the thing.

MK – Yeah, and it was fun. It was fun! And it was insightful…

TS – It is a trusting and intimate act to give someone 500 photos off your phone as well to go through.

MK – For sure. For sure. There was a pre-… before I was officially commissioned by Book Works, and by the Mosaic Rooms to do the book, Mahmoud and myself met and spoke. Just spoke about the project and about our work. We were in Berlin, actually. I happened to be visiting – which is where he is based – he knew that I was there. So he asked to meet me. That initial meeting really just set the tone for this seamless collaboration. Obviously, a huge amount of trust is needed to kind of hand over such material.

TS – Just checking the time…do you wanna? So obviously in this book, it is very obvious that there’s a narrative; you’re creating the story of this guy, or Mahmoud is creating the story of this guy through the installation, and through the book and through your design, you’re shaping that narrative, but I think you’ve said that it’s an approach you take generally to book design. I wondered if you want to say a bit about that?

MK – I really see book design, in a way it operates like a story or like a song. You have to always understand for this project, what is the tempo? What is the rhythm? Is it something that is flowing at an equal pace? Or does it have big contrast? Does it go up and down? Is there a lot of drama? Is there a lot of contrast? Is there humour? Or is it something where the personality of the book needs to go into the background and let the text speak, or the images speak? But this is definitely regardless of the type of book, because I’ve done cookbooks, I’ve done exhibition catalogues, I’ve done artists books, I’ve done more academic books, and they all require a slightly different approach. But what is consistent is, how do you take someone on a journey from the cover? So for example, in this case, we’re already saying there’s something about a person, there’s something about intrigue, there’s something about not giving you any information, the minimal amount of information versus… (23:10)

TS– I should say, by the way, that my job is communications and marketing. So I’m the person who’s always like, ‘you need to put the title on the cover!’ [laughs].

MK – Yeah yeah yeah.

TS: But for me, this is a really successful book, because it has that. It is the object, it is not covered in text. But then because of this, it’s still striking, it grabs you, and it’s got the title on it. So for me, that’s the perfect…

MK – Thank you. I mean, this was a hassle. I mean, as you probably know, this was a complete hassle to create too.

TS – because it is sustainable. I should say that we didn’t want to…

MK – It is yeah, we managed to find a sustainable, plastic bag. Well by sustainable, we mean biodegradable plastic bag.

TS – Sustainable is a bad word.

MK – But yeah, exactly! It is the idea of what story are you trying to tell? Because there are different schools of thoughts and designers. There’s designers who feel like their personality, their input needs to take the backseat and you let the material speak for itself. You let the text speak for itself. I’m slightly of the school of… when people come to me to collaborate with me on a project, they are not just coming to me, for me to provide them with a design vehicle for their work. I partake in this process. So my voice is also partaking in this process. I’m an added layer to this design process because I feel whether you like it or not, your voice is there, so you might as well claim that, own that and deal with it. That could be a very quiet voice, but it is there. The most successful projects I’ve done were a result of continuous discussion with the artist. Or with the curator or with the writer. (25:08)

TS– Well, that leads me on to what I’ve been very restrained in not asking about for the first 30 minutes, which is the big, big Rihanna coffee table book you did. I don’t know how much you got to talk to Rihanna about design while you were making it? [laughs]

MK– I mean, there was a lot of mediators. For context, as my final project with Barnbrook, the former studio I was working in, I was commissioned to design the Rihanna book, which was a book commissioned by Phaidon, the book publishers and Fenty, which is the company that Rihanna started to run her business. They came together to create this coffee table book that would chronicle her, you know, as you can imagine her insane life between I think, 2013 and 2019, or 2018. I think they wanted to round off that era of her life via this photo book, which is, interestingly enough, very much similar to what I did with Mahmoud. Obviously, very different scale, but I was given a hard drive of thousands of images, and I was asked to create a book out of it. And this is not— and again, you are making choices and choices are political. When you make these choices, you’re saying something very specific about that person. So what is it that we were trying to tell about Rihanna? The world knows that she’s a superstar. They know she’s famous and popular and beautiful and successful and talented. But what did we want to say about her in this book? I think it was very interesting to have that negotiation between myself and the team who was putting it together where they were really uninterested in highlighting photo shoots, and red carpet images, because they were like, “the world has already consumed this information. We want them to actually understand what goes into the making of a mega superstar.” So there was a lot of backstage photos, intimate images of her with friends and family and on vacation. And then this idea of rhythm, and this idea of storytelling, or of a song comes back into play, because I wanted to show that she’s also quite subversive and funny and weird and like not, you know, just a typical gorgeous, amazing superstar. And language went in. There was texts that I introduced into some of the spreads to kind of highlight some aspects.

TS– I think if there’s one popstar that I would want access to their phone, camera, album or whatever, it’s probably Rihanna. Like, she definitely seems like she’s got the most interesting stuff going on.

MK– I actually have it here for context. It is really big. For comparison, this is the smallest and the largest book I’ve worked on.

TS I feel like you could fit six of them on the cover.

MK– Oh yeah for sure.

TS– But also, I mean, it is similar, obviously, in the idea of constructing a narrative about this character, but you know, also because in Mahmoud’s work, the character is not a real character, but it is drawn a lot on real life. And I guess it’s kind of comparable to like, you know, which Rihanna do you want, you know, how much is it mediated? How much is it fictionalised almost? You know, in general, and in the book.

MK – There’s no such thing as the real story. There’s no such thing as 100% truth. Truth only exists as the multiplicity of perspectives of everyone together, and no one has that kind of knowledge. I never attempt to kind of present like, “This is it. This is the story. This is the full story.” Everything is an interpretation. So once you let go of that baggage that you’re trying to kind of show something genuine or truthful, which to me doesn’t even exist, just own it and decide what is it that you want to show? And then you work with that as your brief.

[29:41]

TS– Do you think that applies to both to design and to narratives itself? Like…

MK– For sure. I mean, every choice you make as a designer: the font I choose is going to decide whether the tone of this book is one that is trying to be classic, one that is trying to be…am I trying to make it difficult to read? Am I trying to make it in your face? Is this font trying reference some historical thing? These are all choices. Even the size of the image on the page, whether it is a tiny image with a lot of white space around it versus, for example, let’s go back to this. This is another artists’ book that I did for the National Gallery and for artist Ali Cherri earlier this year [holds up a copy of the Ali Cherry book]. And then let’s bring this big boy [holds up a copy of the Rihanna book]. So here, there’s an image full bleed with a big bold text running straight across, it’s glossy, it’s really trying to be like, you’re not going to miss this, wherever you see it. Versus this book, you have an image inset with a lot of white space, very delicate typeface around it, it tells you a completely different story. Give these two books to different designers and then they’re gonna come back to you with a completely different solution. But that solution then exists in real life, these books become part of popular culture, and it starts saying one form of truth, or one part of the story. So every decision is actually what I call a political decision.

TS– That leads us nicely on to talking a bit about political design, but also actually, we wanted to talk a little bit about the economics of graphic design and, and different types of work. Obviously, you were at Barnbrook, which is a very prestigious agency. That is where you did the Rihanna book. Now, obviously, people might assume working on a book like that is gonna pay your rent for the next ten years [both scoff]. But if you are working for an agency, you’re basically just paid your salary right?

MK– Well, there’s two parts of the story. The first part is I chose to work at Barnbrook specifically because I felt like my principles were aligned with theirs, I knew that it is a studio that has a long history of political work, of having its moral compass very visible. That refused work from questionable clients. And that it engages with nonprofit work when needed. So I knew from the get go, that is what was the most important thing for me at that point in my career. Unfortunately, working primarily for non–problematic clients, particularly in the art world, is not your way for wealth and fortune. With a project like this— just to say that it is not this multimillion–dollar studio that is just banking it in.

TS– Yeah yeah yeah.

MK– Then with this project, I was an employee at the studio, so you don’t get commission. It is not like in other businesses. I got my salary at the end. My modest salary at the end. So no, doing this book gave you know… It is a wonderful way to feel like…It’s the first time I had work being shown in the media, being associated with this global superstar. It does come with a certain level of visibility, but finan— and maybe it will generate work into the future. But in that moment, no, there was no rent being paid beyond that month.

TS– Yeah, but you do get to be associated with Rihanna forever. I guess that is something.

MK– Which I’m totally fine with. Full disclosure, even before the book, I was a massive fan. So the little teenage boy was elated.

TS– I’m going to be claiming two degrees of separation from Rihanna by you now [laughs].

Let’s talk about Takweer. I’m just gonna drop a link to the…[34:29]

MK– Let me share it actually. So Takweer is a project that I began at the very end of 2019. I was still working at Barnbrook at the time, but it was around where I felt… So just for context, I’m from Beirut, Lebanon. This is my kind of background, and I am a gay man. I loved my work in my studio, but I felt like there’s a big chunk of my identity that I just was not engaging enough with, which was kind of the catalyst of starting Takweer. Takweer is a platform where I aim to archive, collate and curate a queer reading of Arab history and pop culture. The first iteration of it is this Instagram page where I tried to collect things, whether it’s artwork, historical news, cultural references, clips from television shows, where perhaps, a queer character might have appeared. Or, in this case, there’s this drag queen [Bassem Feghali] with Sabah, which is a Lebanese diva, and they’re both being together. It talks about our own queer icons, for example, this is Etel Adnan, who passed away last year, a very prominent painter, who has lived her whole life with her partner. This information is available. It is there. No one is saying I came up with this. The difference is, I’m trying to put it in one place where us—people from the Arabic speaking region who do identify as queer can have an accessible archive, where we feel like our own version of what queer is can be accessed. Again, this is never the full story. This is part of the story. This is my perspective for now.

TS [reading from screen]– And…makhnakh? …is that “sissy”? [in Arabic]

MK– “All hail the sissy boy!” This is actually part of an ongoing research which is leading into the book that I will be working on. I’m very interested in language and multiple meanings and wordplay and puns and context and nuance and how words change meaning from one place to another. As part of this research for Takweer, I have been collating a glossary. I have been collating a glossary around queerness. As in, how do you refer to someone who is queer, from across the Arabic speaking region? And again, for context, Arabic is a language, but every country that speaks Arabic, speaks it in their own way, and dialects vary massively. So I’m interested in the landscape of lexicon around queerness in the Arab world. So I started asking people like, “how do you say someone’s gay? Or how do you say someone’s a lesbian? Or how do you say someone’s trans?” Not just in the politically correct way. I’m not just looking at ‘what would the activist say?’ I’m interested in what is said in the streets, and in schools, and in families and in a derogatory way, and in an endearing way. I’m starting to collate those. So this post, for example, was a preview of this research where it started with, “how do you say ‘a sissy’, someone’s a sissy? How do you refer to a camp or an effeminate man or boy?” And this is not to say that those words are okay, some of them are very triggering and traumatic. But by putting them out there for public consumption, we kind of take back the power— take away the toxicity and try to claim it as our own. To actually start to understand, what do these words mean? For example, the word we’re seeing now, “maye3” or “mayeh”, which is used a lot to refer to an effeminate or a camp boy, it means fluid, swaying…

TS –Yeah.

MK – Because apparently, the way we walk is always fluid.

TS – And it’s the same root as water, right?

MK – Yeah, yeah yeah, exactly. Or “tante” – it’s the French word for “aunt” which is an auntie or like a queen or a pansy. In this sense, it tells us a lot about the history of the region, because this word specifically, is mostly used in the Levant region. So in countries like Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan, and the reason why we’re using a French word is because we were under French colonialism. So these words starts telling you a lot about who we are. There was a companion post that I did, which was also ‘All hail the tomboy’ which looks at the flip side of it. How do you say tomboy in these different countries as well? So this is part of this ongoing research and I’m currently in the process of designing the book, which hopefully will be published next year. It will be the first physical project to come out of Takweer outside of the Instagram page. [40:12].

TS – Really exciting, I can’t wait for that. I mean, as a queer person who’s learning Arabic it’s quite useful on a very practical level for me [laughs] but it’s also like you say, so rich, and I think particularly with Arabic, particularly because the different kind of cultural contexts and dialect and, and stuff like, yeah, there’s just so much there about how people live. And I mean, I think we’ve sort of maybe touched on it briefly but yeah…it’s very, very different being in the diaspora, sort of, you know, my arab heritage, and I’m queer, but I’ve never lived in the Middle East I’ve never like, and this stuff it’s not, it’s not in my view, in the same way…But it’s really special to be able to kind of get that culture in Instagram.

MK – Absolutely. I mean, It’s funny, because I started the project for myself. I started it as a space to collect my thoughts, as a space to collect my references, because there was so much being said, between myself and friends that would get lost, and which generations before us, you know, their jokes, their references, the stories they told. Queer people who are living in spaces that are still hostile to their queerness leave very little behind. They have very few traces. It’s crucial— I mean, I’m in a privileged position now that I’m out in public and I don’t care who knows, or what they say, or whatever. But having that privileged position, I first of all, I understand this privilege, and second, I feel like I’m capable of trying to be vocal about it. And using my design skills, and my storytelling skills to go back to that, to now really talk about myself and my experience, and those whose experience is similar to mine.

TS – And also I guess it links back to Fantasies on a Found Phone as well. I think you mentioned in the launch the other day, archiving this stuff is particularly important when it’s not always safe to keep an archive or to keep a record. Things are naturally sort of fleeting on social media anyway, but yeah, like the amount of times I imagine people might have had to just delete their whole phone to cross a border, to go to a protest.

MK – For sure. I mean, for political reasons, for reasons relating to your sexual or gender identity, we are constantly erasing, we’re in this constant state of erasure, to protect ourselves so that the authorities don’t find this implicating thing you have on your phone, whether it’s because of your allegiance to a certain political agenda, or because of the fact that you’re queer. So, we’re always deleting— actually, a couple of years ago, an Egyptian activist, a queer, communist, feminist, Egyptian activist Sarah Hegazi, who was exiled from her country because she flew the rainbow flag at a concert. The story goes that as soon as she heard the knock on the door, she ran into the bathroom, locked herself in, deleted all the apps, wiped her history, and then told all of her friends to do the same. This just give you a little bit of a capsule of the kind of erasure, self-erasure we are doing.

TS– I think yeah because people talk about it, you know, it seems we talk about it in sort of OpSec terms, like, “Oh, you shouldn’t keep stuff on your phone.” Or it’s good to have [inaudible]. But the actual reality of that, you know, it sounds sort of in abstract it’s like, oh, it’s good practice or whatever, but the actual reality of having to delete everything off your phone, like—

MK– it’s insane

TS– Yeah.

MK – Crazy. Um, so yeah, Takweer aims to maintain part of that history to a degree. 44:35

TS – That kind of nicely leads us on to I guess, the last thing I wanted to talk about, and we are running out of time, so if people have questions, by the way, you can either pop them in the chat or we’ll open up in a bit.

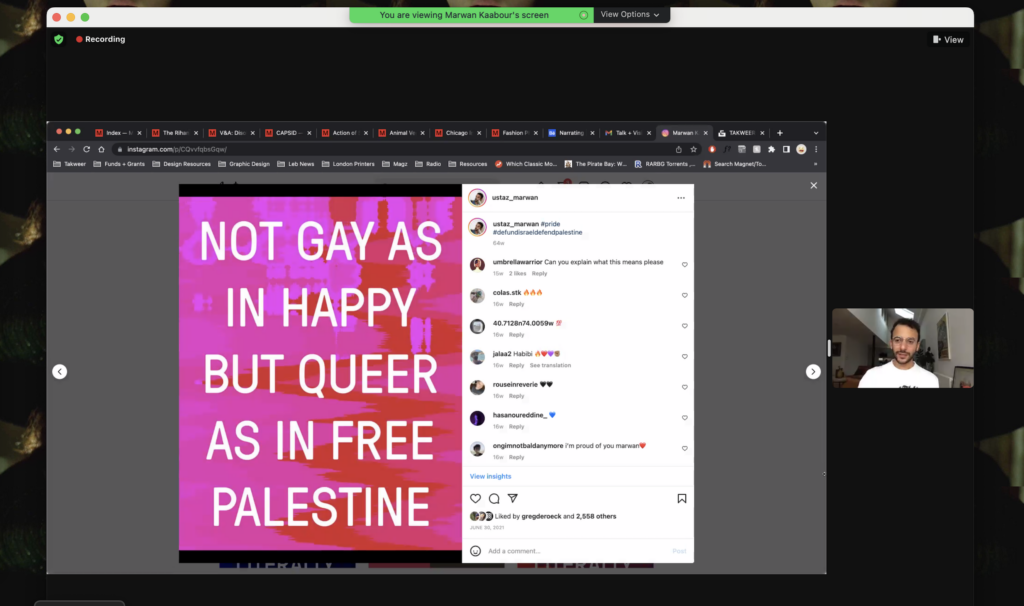

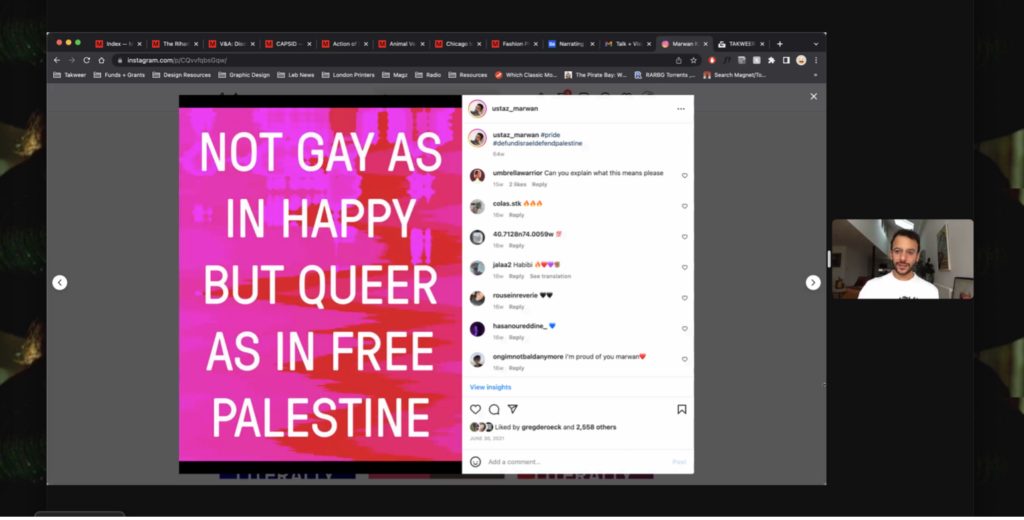

Just finally, when I first looked at your Instagram page, the first thing that grabbed me was that you’ve done some political graphics, particularly about Palestine, in solidarity with Palestine. I am involved with some cultural boycott stuff here, started a campaign called ‘DJs for Palestine’, which pretty much played out on Instagram. We had a little red, pink graphic with a statement that went everywhere. Yeah, I mean, talk about it. I think some of yours went viral, right?

MK – Yes. So this was around a year ago, during the latest assault on Palestinian land, it was around May 2021. And around that time, there was a lot of discourse. Well, I think my frustration was me as an Arab individual who feels very strongly about the liberation of the Palestinian people, living in the UK, I was always surrounded by friends and acquaintances who somehow sometimes aligned with me politically, but were so afraid of speaking about it, because they lacked the tools, the linguistic tools to vocalise their opinion without them coming across as problematic or antisemitic or so on. To me this correlation is nonsense, because when you call up for the liberation of an occupied people, it’s the same as calling for the liberation of women, of queer people, of people of colour, this is all the same thing.

TS – Yeah, its unconditional.

MK – Yeah yeah, and I just wanted to, through very simple posts that literally try to present you with facts, just give you facts. It’s not even telling you this is an opinion. I’m just saying, these are what these words mean, and it’s up to you to choose them, to make your opinion. But don’t conflate them, because the conflation causes problems, and I think it resonated so much. I mean, as you can see, this one was liked by 150,000 people, I think it was shared thousands and thousands and thousands of times. I think it resonated because so many people were hungry for that information. But what was the trick here is, I’m also a designer, so I was able to write it in a way that is accessible, that is impactful, legible, and attractive. I mean, I know, it’s not the point here—

TS – No, it is the point I think,

MK – but when it’s striking, you’re drawn to it. This is what the trick here is like, Oh, when I use my skills to make a political statement, things can resonate in a wild way. And then it ended up triggering a whole series of graphics that I produced that during that time that were continuously going viral.

TS – I think it really does matter. The statement obviously, is the thing, and like, as we did with the ‘DJs for Palestine’ thing, you can just put some bold text on a bright background, and that will do the job. But like, people won’t be drawn to that beyond what it says, or what’s this pink thing all over everyone’s screens. Where as that, I see that on a feed. And I’m like, “Okay, I agree.” And also, it makes me want to actually…

MK – …know more

TS – yeah [48:33]

MK – Yeah. So, just to kind of make a final point. This goes back to a very famous manifesto, called ‘First Things First’, that was signed by many prominent graphic designers at the time, which says that graphic design is a tool to communicate, and it should not just simply be used to communicate about the branding and, you know, gorgeous packaging for perfume, and Nike and Coca Cola, and big campaigns to sell you stuff, – which I get, this is the world that we live in– but we also have the responsibility to use those tools to tell the stories that do matter, that can change lives. And I try, it’s difficult, but I try to uphold those principles in my work as much as possible.

TS – That’s a good note to end on I think. Can we have any questions? We can either put them in the chat or ask to unmute.

Naïma (audience) – I’m curious to know who will publish the Takweer book, but can you talk a little bit about that?

MK – I don’t have a publisher yet.

TS – Here’s your chance, you can make a pitch!

MK – I started the project as a completely independent project. I’ve been able to secure funding to pay the people who are writing the essays and editing and translating and proofreading. I’m doing the design myself. I was initially of the thought that I would like to self publish it, but I am quickly understanding that this requires a far more engaged and involved distribution network. And, I would like to have a publisher, I don’t have a publisher yet. This is a conversation that I haven’t really begun properly as I’ve been really busy with other projects. I would like to find a publisher, but the nature of this publisher also matters because I don’t think it lends itself easily to a big commercial publisher. In an ideal world, it would be lovely for an Arab publisher to take it on. But I’m not sure the logistics of that, but it’s an ongoing discussion that I am hoping to deal with or engage with more seriously in the next few months. But thank you for that question. Really valid, I’m thinking about this a lot right now.

TS – Yeah, well, everyone’s gonna want to read it. So you’re gonna have to—[laughs]

MK – I know, I know!

TS – I’m gonna keep asking you every time I see you. [laughs]

MK – I mean, also just to say the book will be… it concerns the Arabic language. So naturally, the primary language of the book is in Arabic. So it will include the glossary, which is around 400 words and terms; it will include two essays reflecting on the findings of the book; a transcribed panel discussion between activists from around the Arab world talking about queerness, language translation, and how these things matter to the way we operate; and then 20 to 25 of the terms will be illustrated in a gorgeous way. So it’s going to be a proper, fully–rounded publication and I understand there is going to be a lot of interest in it. So it is going to be a challenge to try find the right publisher that can give it justice. [52:16]

TS – Anything else that you would like to plug or promote while you’re here since this is about plugging,

MK – Oh yes actually. On Thursday, I will be heading to Berlin to take part in Soura Film Festival which is a film festival that highlights queer filmmakers and creatives from the SWANA region. I’ve been invited to curate the two panel discussions that happen in–tandem with the festival. So I will be there. I’ve organised the discussions and I will be there to moderate them in person, which will take place on October 1st and 2nd in Berlin. I’m just going to write the name of the festival if you’re in Berlin and would like to check them out. Please join, otherwise—

TS – Here’s the link as well.

MK – Oh, yes. Otherwise, this just opened last week, I also designed the book for the new V&A show, Hallyu, that explores Korean culture. It’s a really fun book. Very different, but that just opened so check it out, get the book, buy it, enjoy it.

TS – Thanks so much. We are doing these every month. In theory, they’re the third Wednesday of the month, although today’s the fourth Tuesday. But the next two will be on the third Wednesday of the month. And the next one is with Fraser Muggeridge on the 19th of October and then on the 16th of November we’ve got Sara De Bondt. So yeah, look out for those. Thanks, everyone for coming and we’re gonna get these archived online.

MK – Thank you, cheers!

TS – Thanks a lot!

Order the second edition of Fantasies on a Found Phone here. Follow Takweer on Instagram.

The Queer Arab Glossary is now out, published by Saqi Books, and getting rave reviews!