Visual Pleasures: Juliet Jacques

This is an essay commissioned by Book Works in response to Diana Georgiou’s novel, Other Reflexes. We asked five writers and artists to each respond to one of the book’s chapters, each themed around a particular sense, with a text-based work of some kind. In this photo essay, Juliet Jacques responds to the prompt of ‘Visual Pleasures’ with an account of a trip to Nicosia in 2022.

Nicosia 2022

I arrive in Nicosia as I do everywhere, camera ready, wanting to create a visual diary of a city. Not just its permanent or its long-standing features, such as its rivers or coastlines, or its buildings, monuments, or public art, but also its ephemera: graffiti, posters for gigs, plays or exhibitions, players or crowds at football matches, anything else that places it in a particular moment. I know Nicosia will be a visual overload: as I fly into Larnaca – the nearest airport, as the capital’s has been disused since the Greek far-right coup and subsequent Turkish invasion of Northern Cyprus in 1974 – I reflect that, while most British people spend holidays here at the beach, I’m likely to wander around the city looking for legacies of my country’s colonialism and how it impacted upon a still-present conflict, like I did in Belfast and Hebron/Al-Khalil in 2017. The only beach I’d be interested in visiting is at Varosha, near Famgusta in the Northern part of the island, a popular resort until it was hastily abandoned in 1974. The Greek residents hoped to return within a few days but it’s still closed, and is apparently an eerie time capsule: photos from the perimeter are forbidden, and trespassers risk getting shot.

I’ve come in February precisely to avoid the warm season, so I’ll have more energy for walking. I’d also wanted to see the politically-charged football match between Omonoia and APOEL, whose rivalry is based not on the Greek/Turkish divide (there are separate competitions) but on familiar ideological lines: Omonoia are traditionally Nicosia’s left-wing club; APOEL are aligned with the right. I was looking forward to visiting the country’s largest stadium on the outskirts of the capital, but it got rescheduled after I booked my trip. Instead, as the taxi drives past, I see the floodlights glaring as APOEL’s First Division match against the equally right-wing Anorthosis Famagusta, who haven’t played in their home city since 1974, draws to a close. I probably would have gone if I’d arrived in time, I think to myself, but as we enter the city, I see a hastily scrawled ‘APOEL’ above a crudely drawn swastika and reconsider.

The next morning, I have breakfast at Zaha Hadid’s recently completed Eleftheria Square, with its concrete walkways, palm trees and fountains. Hadid won a competition to redevelop the space, below the city’s medieval Venetian walls, in 2005, but it was still a building site when the financial crisis of 2008 hit so hard that the government were forced to raid private bank accounts. It ended up going twice over budget – from €20m to €40m, and to some extent, a symbol of a country more interested in impressing other nations than looking after its poorer citizens, let alone migrant communities. Guiltily, I find that it’s a rare piece of contemporary architecture that I like – it’s spacious and elegant, and unapologetically futuristic. I look up at Jean Nouvel’s Tower 25, with its perforated walls and wide balconies with plants spilling out, and then head back into the old town. I walk for hours, seeing the excavation site at the 12th century Palaion Demarcheion, the city walls and the ancient Famagusta Gate, the Church of Ayios Antonios and the Ömeriye Mosque. I find monuments to Greek poet Kostis Palamas and Cuban poet and nationalist José Martí, and statues of guerrilla fighters Markos Drakos and Iakovos Patatsos, who died in the struggle against the British occupation in 1955-59, which secured Cyprus’ independence in 1960. This leads me to Ioannis G. Notaras’ extraordinary Liberty Monument, unveiled in 1973, just before EOKA B (the Greek Cypriot paramilitaries) turned on Archbishop Makarios’ government and launched the coup that overthrew him and prompted the Turkish invasion. As a result, its precise meaning is undecided, and contested, loaded as it is with shiftable symbols of oppression: a Lady Liberty-type figure on top; two men pulling on chains just underneath; and lowest, men and women praying at the bottom of a staircase, outside a prison cell from which several statues emerge. It’s not subtle, but its sheer scale is impressive, and I can’t fail to stop and look every time I walk past.

A year after Notaras’ monument was unveiled, the UN Buffer Zone or ‘Green Line’, established in 1964 and patrolled by the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus, was extended across the island, cutting through Nicosia airport and Varosha, and the city calls itself ‘Europe’s last divided capital’ (presumably not counting Belfast). The border wall was opened in 2003, and it doesn’t take long to walk there from my hostel. Approaching the checkpoint from the main street, I see an abstract sculpture with metal rods rising out of tree trunks cut to look like bouquets of flowers. It’s by Cypriot contemporary artist Theodoulos Gregoriou, commissioned in 1995 and simply titled Resolution.Walking the Line, I stop to look at a poster that shows the Turkish-occupied part of the island in blood red. I have just taken out my camera when a soldier pops up next to it, brandishing a gun, and swiftly put it back in my bag.

The buffer zone still has plenty of barbed wire and concrete barriers, but you only have to walk a few metres to go back to the tourist traps: Cristina, a friend of a friend who grew up in Nicosia and who accompanies me throughout my trip, tells me that the ice cream parlours and the tastefully named Berlin Wall kebab shop have sprung up in the last twenty years. When she was growing up, the only thing that dared open nearby was Ta Kala Kathoumena, an anti-fascist bar that I had already noticed, having asked her what the place was with the striking mural of Nelson Mandela, opposite the bougie arts and crafts shop in the shopping arcade. She got her education there rather than at school, she says, not just about the conflict that dominates narratives about the island’s politics (such as Michael Cacoyannis’ Attilas ’74, which I watched just before setting off) but also about anti-racism and anti-fascism, literature and art, comradeship and love. I’m surprised it still holds its own in an increasingly gentrified space, but when I return in the evening, it’s full of people passing this knowledge across generations, maintained by and nourishing the activist community in an area that tries to both highlight its historical trauma and to downplay it.

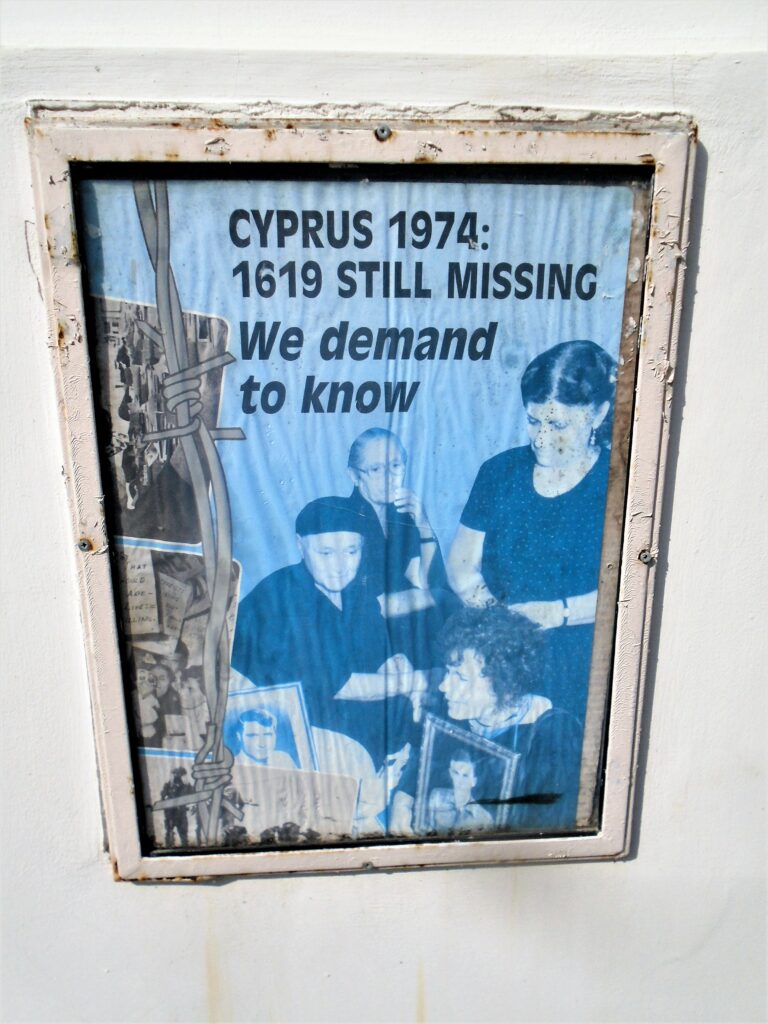

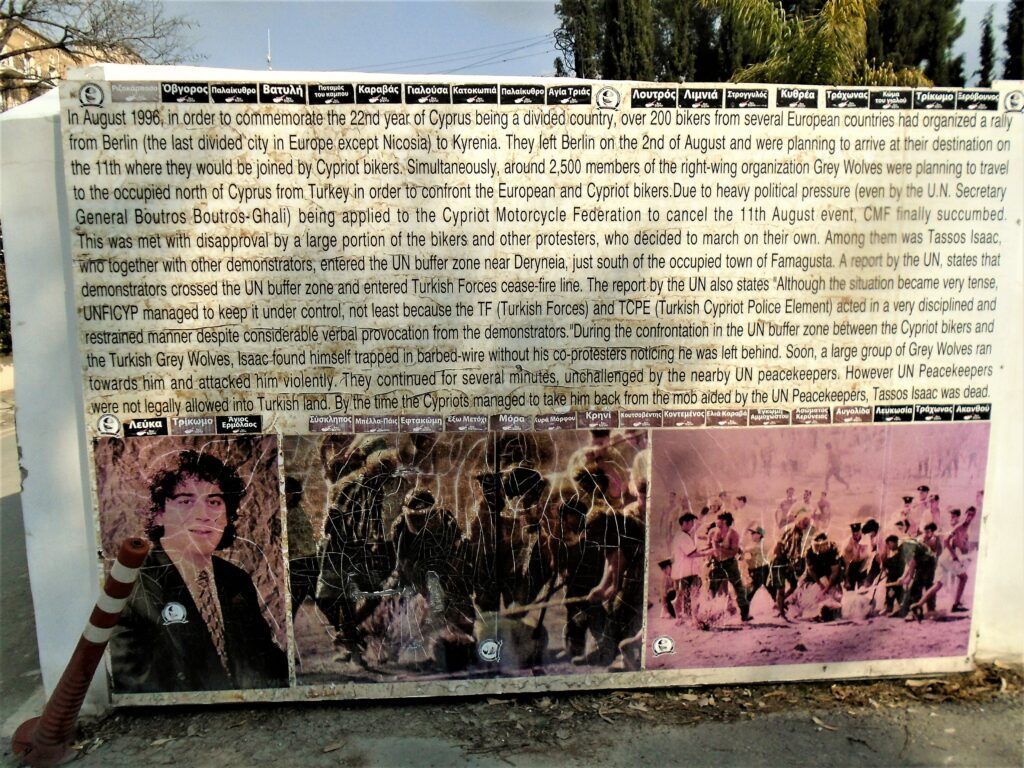

I spend my Saturday on the Turkish side – known locally as Lefkoşa rather than the Greek, Lefkosia, or the British name, Nicosia. All around the border, on the Greek side, there are posters about people killed by the Turks – one to remind visitors that hundreds went missing when they took Northern Cyprus in 1974, and others with detailed stories about Tassos Isaac, killed by a Turkish fascist group called the Grey Wolves in a confrontation at the Green Line in 1996. I pass the Ledra Palace Hotel, a huge, deluxe building by Benjamin Günsberg in 1949 and caught between Lefkoşa and Lefkosia twenty-five years later. The whole stretch is devoted to conflict resolution that doesn’t seem to be forthcoming, and when I reach the other side, I’m not sure whether to focus on what seems different, or what looks similar.

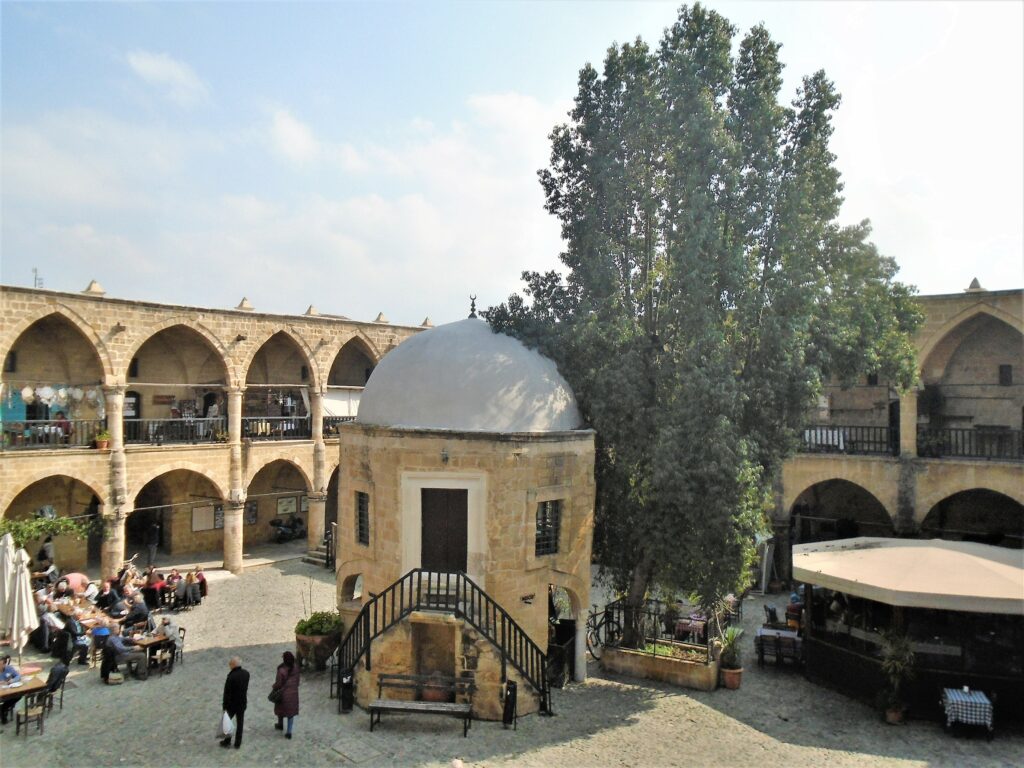

Obviously, different people are commemorated – there are several statues of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as in all Turkish cities (and in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, when I visited in 2018). There is a prominent Turkish Martyrs’ Monument, a dignified stone obelisk on a black plinth dedicated to people killed between 1570 and 1974. The Museum of Barbarism, about the family of a Turkish military doctor attacked by Greek Cypriots on the ‘Bloody Christmas’ of 1963, was recommended by a Turkish Cypriot friend from London, but it’s closed, so I look for something else to do. I visit Büyük Han – the old market that looks like the traditional city centre, and stop for a Turkish coffee in a bookshop called Rustems.

In the café, it strikes me: it’s Saturday afternoon. Maybe there’s a match? I know Anorthosis, APOEL and Omonoia from European competitions, with the two right-wing clubs making the Champions League within recent memory. The Cypriot First Division is all Greek, and for the frustration of missing the Nicosia derby, I had the meagre consolation on Friday night of going to see two mid-table teams, Doxa and Pafos, draw 1-1 at the Makario Stadium. But there’s a Turkish league too, not recognised by UEFA or anyone else, with the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus unacknowledged anywhere except on its side of the Green Line and in its parent country. Finding information about the KTFF (Kıbrıs Türk Futbol Federasyonu) Süper Lig is difficult, but there’s a website in Turkish and English, although the fixture information is hard to parse. As a result, I go to the Gönyeli Stadı on the wrong day – players are training but there’s no match, and I get a taxi to the Lefkoşa Atatürk Stadı for a match between Yenicami Ağdalen and Mesarya, both names utterly unfamiliar to me.

Arriving late, I walk straight in without a ticket – a nice contrast to the Doxa match, where I nearly didn’t get in because I had to log my personal details on some inscrutable website before I could buy a ticket. Yenicami AK are already 1-0 down. There are a few hundred people in an open stadium that holds 15,000, and the standard is pretty low: over the last couple of years, I’ve watched matches in the top ten tiers of the English men’s pyramid, and I’d put these two teams, made up exclusively of unfamiliar Turkish Cypriot players, near the bottom of it. At half-time, Yenicami AK bring on a winger called Hascan Kırmaz, who catches my eye. He lines up a corner on the side nearest me, and my well-trained eye for an image makes me rush for my camera. In front of an empty, crumbling stand, Kırmaz shapes up to cross, with the Kyrenia mountains in the near distance. I can see the Northern Cyprus flag that the Turks have painted on there, with the legend ‘Happy is the man who is born a Turk’ next to it, visible at all times from the Greek side and clearly meant as a provocation.

Soon after, Kırmaz equalises from the penalty spot. There’s still not much fervour – neither side are in the title race, and winning that wouldn’t lead to anything bigger anyway – and there isn’t much shock when Mesarya, the better team, get a late winner through midfielder Ertaç Taskıran. Walking back towards the checkpoint, the reminders of the historic violence and military presence become more frequent, as they had on the Greek side, with warnings not to photograph the Turkish army bases. The closer I get, I wonder why I can’t ever take a holiday in the conventional sense, and instead want to walk around, alone, to seek out sites of trauma. My conclusions, I know, will be largely unfavourable, but I don’t get that far as I have no community here, and no lovers anywhere, with whom to share my thoughts. I kept the visual diary on my hard drive, and now, 18 months later, I’m sharing it with you, in the nervous knowledge that you will likely be the judge.

Juliet Jacques (b. 1981) is a writer and filmmaker based in London. She has published six books, including Trans: A Memoir (2015), Variations (2021) and Monaco (2023). Her fiction, journalism and essays have appeared in numerous publications, and her short films have screened across the world. She teaches at the Royal College of Art and co-hosts Novara FM.

Other Reflexes is out now – order it here.