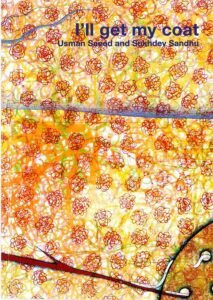

Extract from our Book of the Month, I’ll Get My Coat by Usman Saeed & Sukhdev Sandhu

A writer, an archivist and a painter set out on foot to explore the landscape of Britain. Eschewing the heritage trail they walk the streets of Dalston and Stoke Newington, the cemetery in Ilford, and through Manningham, journeying after the Muslim vernacular across the landscape − mapping Asian history, culture and ruins in Britain.

Below is an extract from I’ll get my coat by Usman Saeed and Sukhdev Sandhu (2005). Published in 2005 as part of Scape Specific, a project curated by Sara Wajid which explored the evolution of a Muslim vernacular in the British landscape. It is currently our Book of the Month – order it with 30% off for the rest of August. With these older titles they are unlikely to reprint, so get the final copies while you can!

On General Election morning I’m wandering around Halkevi, a Kurdish and Turkish Community Centre that can be found along a busy street full of budget supermarkets, spartan cafes, nail design salons and boarded-up Edwardian chemists in the Stoke Newington area of North London. It’s an imposing building, an old Jewish garment factory whose industrial grandeur is not entirely smothered by the tarpaulin and scaffolding that covers much of it as it undergoes renovation. By the late 1970s the ground floor was being used as a wedding venue by Turkish Cypriots, many of whom still recall the tunes and colour supplied by bands such as the Butterflies and the Cyprus Quartet whose musicians were local tailors and carpenters.

In those days it was a place of joy. That changed in 1986 when it became a hub for tens of thousands of Kurdish men and women escaping the torture and government clampdowns back in Turkey. It was a home for those without a home, for those who dreamed of a homeland. A community of sorts was forged here, but one that was as much coercive as voluntary: centre officials would strong-arm locals into paying weekly levies. It became a PKK stronghold, a training camp for radical activists and future guerrillas who were taught to question their family loyalties and to regard them as less important than nation-building. Women in the area were so anxious that in desperation they tried to hide their sons from the Centre ’s panoptic eye.

By the mid-1990s Special Branch had taken to raiding the Centre. Today there are no security guards or amateur militia manning the front door, though a huddle of middle- aged men sipping tea around a table gaze at outsiders with suspicion as much as surprise: this is a self-regulating environment, one whose dimly-lit hall recreates the atmosphere of a provincial museum, where everyone knows each other. The snooker table, a near ubiquitous feature in Turkish and Kurdish social spaces, is deserted. On a pinboard are fastened notices offering cheap leases for kebab shops in Hull.

The sense of hushed desertion doesn’t feel in any way intimidating; rather, it sets the stage for the contemplation of a striking section of the wall on the right-hand side of the hall. Here, protected by cheap plastic, are photographs of around fifty Kurdish men and women who have been fighting against the Turkish state. Young, mustachioed men in camouflage squatting on the ground; a carefully composed portrait of a slim-hipped young woman standing in an orchard; a group of soldiers hiding in a bunker; an enlarged photocopy of a broadsheet picture of a fighter with the newsprint on its reverse still visible. Some of them look barely out of their teens, while one resembles a septuagenarian philosopher-poet. Some look defiant, others smile or raise V-signs. Most carry rifles.

What they all have in common is that they are dead. And that they are all related to families who live in this area of London. Above the photos is a sign, in Kurdish: ‘We will not forget them.’ This is a martyr’s memorial. A wailing wall that creates a foundation narrative for what it means to be Kurdish: the importance, and the inevitability of death. The dead are not departed, it insists; they are among us, watching over and for us. The wall, seen alongside the photos of the jailed guerilla leader Öcalan that hang throughout the hall, establishes the dominant mood of grief and collective struggle that underwrites this community centre.

The Kurds who attend this centre are Muslims, but religion plays little part in their lives unless they’re travelling abroad, in which case they use faith as a luck charm and drop in to the prayer room at Heathrow. The Centre ’s events co-ordinator is Yashar Ismailoglu, a Turkish Cypriot ex-soldier and former classmate of Öcalan who came to London during the power shortages of 1972. A poet who has published several volumes, he also set up the longest-surviving Turkish newspaper in the area, as well as a local football team. Activism is his life – and did for his adopted daughter whose photograph is included on the wall.

He is endlessly busy, full of good cheer, known to everyone in the neighbourhood. It’s impossible for him to walk more than a couple of yards without bumping into a friend, colleague or co-conspirator. Yet talk to him for more than a few minutes, and a great melancholy enters the conversation: he dreams, he says, of mountains and of freedom. Here, in England, “What we have lost is our enjoyment of living. It is exactly like a robot here. We come to work, then go home.”

We go to one of the many Turkish and Kurdish cafes that are found in the area. A clump of old and silent men cradle their coffees. “In the social clubs here, it’s just playing cards,” says Yashar, “They don’t even talk. They’re just killing time. There is no fun.” These places, many of them private and many acknowledged locally as drug dens, are far from the classic caffs that get celebrated by the aesthetic moribundists of the capital’s psychogeographic fraternity. They’re refuges from women, mosques for the faithless, retirement homes for the old and fatalistic.

There are few visible traces of the past as we wander around Stoke Newington, Yashar’s memories function as a kind of architecture. As he recalls the protests he led, or huge street marches that Halkevi orchestrated, the streets become momentarily filled up and populated by ghost communities. We observe pro-Öcalan, anti-imperialism graffiti and reflect on how these hasty, nocturnal scrawls represent an archive, never collected and often fly postered over, of local resistance. “They are words,” Yashar hazards, “paragraphs – in the book of the Turkish Left.”

The siege mentality that enabled, however patchily or involuntarily, a sense of Kurdish community is on the wane. London- born teenagers, no longer animated by the dream of returning East, struggle with the law and with their parents. Halkevi, once a self-designated “engine for a Kurdish new republic” and, according to Yashar, local peoples’ “eyes, tongue and brains”, has moved in the direction of being a welfare organisation that deals with spousal abuse, mental health, drug addiction and all the other ailments common among poor migrant populations.

Young Kurds embrace the amnesia of British pop culture, its repudiation of anything so worthy or old-fashioned as politics. Unlike their elders, they’re not assailed at night by dreams of beatings, electric shocks, prison-cell torture. Yashar, who knows that a community is nothing without shared memories, is currently involved in an oral history project that involves the recording of first-generation settlers. The first batch of tapes arrived the day we met, but they proved to be faulty: the lighting was poor, the voices inaudible.

From I’ll get my coat by Usman Saeed and Sukhdev Sandhu (2005). Published by Book Works as part of Scape Specific, a series curated by Sara Wajid, which sought to explore an imaginary map of a Muslim vernacular in the English language and landscape. The collaborators have taken a defiantly parochial focus on the everyday texture of dialects and local inflections close to our hearts. We’re not interested in the construction of British Islam, only the specificity of Mannigham Mirpuris, Essex Punjabis and Kurds from Stoke Newington. Scape Specific is both a record and a fantasy of a Muslim life more ordinary.

Order I’ll get my coat here with 30% off.