Graphic Negotiations #3 – Erik Hartin and Moa Pårup – video and transcript

As part of our series of conversations with designers, Graphic Negotiations, we were delighted to welcome designers, art directors and activists Erik Hartin and Moa Pårup for a chat on Zoom. The original event didn’t record, so they were kind enough to redo their presentation for us. Below is a full verbatim transcript. If you would like a plain-text version compatible with screen readers, please drop us a message here.

MOA PÅRUP – Hi, everyone and welcome. Thank you so much for coming to this talk, and thank you to Book Works for inviting us.

ERIK HARTIN – And so we’d like to start by grounding this talk a bit in the title of the series of talks, which is Graphic Negotiations. Negotiations are kind of a given when it comes to design. Because design doesn’t happen in a vacuum, it’s always a conversation. It can be a conversation between an author and an audience; conversation between an organisation and the public or, as often in this context between a designer and an artist, or artists. And the word negotiations itself also connects everything about our own practice. Because our practice is also a family, and negotiations in short, are kind of part of everything that we did together.

MOA – Right, so, um, for us, having our design practice involves the constant negotiation that we have between our own living situation, which requires money for rent and for childcare, and food, etc. And the impact that our work has, or can have on everyone else, from our community to our planet. We have divided this talk into three parts, but we’ll try to keep it to around roughly 40 minutes. In the first part of the talk, we will present and talk about our work in its context, since we graduated from the RCA about 10 years ago, and up until about three years ago. The second part will be about our awakening. And don’t worry, it’s not a religious awakening. But we do want to warn you that we will be talking about climate change, and its impacts which are bleak. And we’re going to show you images of disasters, which are fueled by climate change, which are horrific. In the third part of the talk, we will talk about how we have shifted our practice since just before the pandemic; our work coordinating the Extinction Rebellion Design Group, and what we hope will happen next. When we started preparing this talk, we realised that this summer marks our 10-year anniversary of working together, and nine years roughly of living together. But in fact, we might have met 25 years earlier than that as we actually lived in the same part of Stockholm when we were kids. Here we are happily unaware of each other in 1986, or something like that.

ERIK – So, here’s another old photo. So these three, Guy Debord and Michèle Bernstein in the middle and Asger Jorn on the right. So we wanted to start this talk by kind of recounting how we came into contact with Book Works. But then, of course, you have to go back even earlier, and so here we are in Paris in the 1950s. So Guy, Michèle, and Asger, as I like to call them, were co-founders of the Situationist International (SI), which was a group of artists and intellectuals who came to define much of what we now understand as late capitalist culture. One of the Situationists’ integral concepts was that of the ‘situation’, hence the name. And a situation to them were moments that were deliberately designed to provoke an escape from reality, or from the capitalist spectacle that we all live in. I’m going to return to this later when we get to Extinction Rebellion. But for now, let’s just say that in 2011, as I was graduating from the Royal College of Art, these three and their merry cohorts were very much on my mind. So this is a book called The Meeting of Failures. It was my graduation project, which was a collectively-written novel by a collective called Everyone Agrees, of which I’m a member. The books were hand-printed on my tutor’s risograph and section sewn together, we made 150 copies. The book itself was a novel, I guess it was quite experimental in the way that it was produced, in terms of it being the fruit of a collaboratively-written Google Doc. And it was partly autobiographical, in the sense that it did describe real people in fictional events, but sort of the places where it’s set, so clubs and performances were different, or sort of…a lot of it kind of happened and all we did was kind of change the names of people. And it was set in the early 2010s, East London art scene.

The design itself was heavily inspired, or copied one might say from André Breton’s, Nadja. So in the slide, on the left, you have Breton’s Nadja and on the right you have The Meeting of Failures. We decided to base the sort of layout of the book using quite a lot of photography. And we use this, and this is true as well for Breton’s Nadja uses photography as a sort of a device to intentionally blur the lines between reality and fiction. And we often use photography in our work, even when working with novels too, as a way to sort of reinforce the realities of narratives, even though they might be fictional in nature. And so, the backdrop of The Meeting of Failures, like I said, it was set in sort of early 2010s East London in the art scene, but the backdrop was the ongoing Occupy protests happening in New York and London and elsewhere. I mentioned the Situationists just now and our book was kind of an attempt to crudely draw and interrogate certain parallels between the ongoing protests that were happening and what that sort of meant, at the time, with the avant garde Paris of the 1960s, going into 1968. The main characters, like I said before, a lot of them were sort of based on people around us, but the main characters were also caricatures of ourselves. So I won’t dwell more on the book, but it serves as an introduction to speak about how we came into contact with Book Works. [06:18].

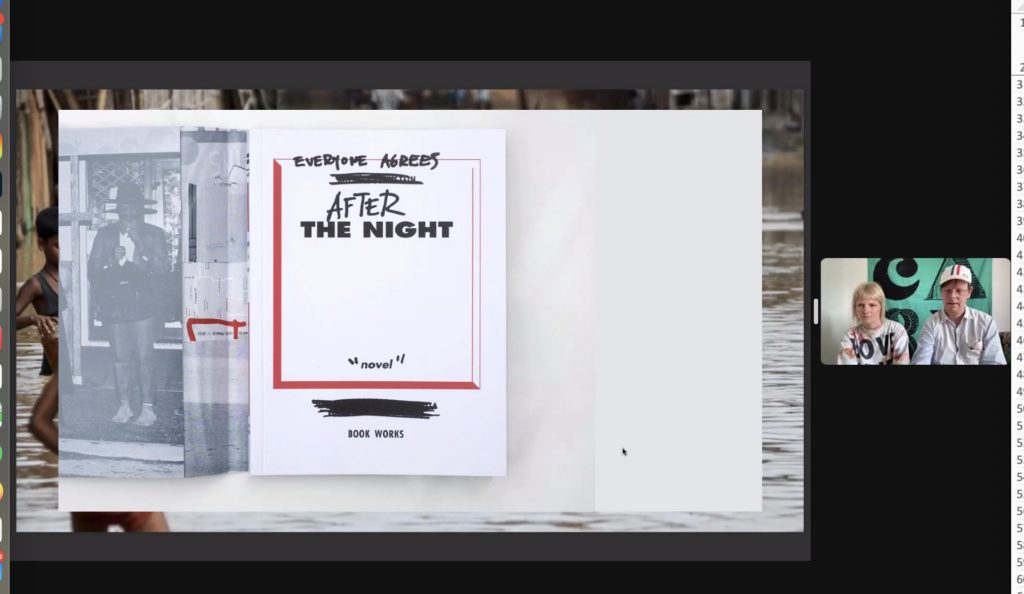

So, we heard about Book Works, commissioning for the series called Common Objectives, edited by Nina Power. And so Michèle Bernstein, who I mentioned on the first slide, wrote two novels in the 1950s, the second of which was called La Nuit, and at the time, it had never been translated into English, nor republished really. And our proposal for Book Works was, quite simply, to find the text, translate it into English and then appropriate it into a work of our own. And we explained in the submission that we hadn’t found the text, we knew of a copy in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France[ in Paris, but we hadn’t accessed it really at all. So the first part of the project kind of turned into a bit of a hunt for the text. And as part of that, I randomly came across Michèle herself in Stockholm, where she was kind of holding a slightly impromptu gathering as part of a small painting exhibition. And I was very nervous when I met her. But in the end, it was quite fun, like, we all got quite drunk, and I was drunk enough to talk to her. And I kind of used a fake name taken from our first book, to introduce myself and I talked about our project and how we wanted to appropriate her novel, and she was quite into the idea. And in the end, I sort of left having convinced her that I was a bonafide Marxist, which is funny, as well as her basically offering up the rights to the translation. And a few months later, we did find a text that we started translating from. But she also found the original copies of the book, and offered us one. So this is the original 1960 edition, I think of La Nuit, which we then appropriated to turn into the cover of our translation, The Night, which was translated by my colleague, Clodagh [Kinsella] and edited by us as a collective. The second part of the project was called After the Night which was then a kind of appropriation of Michèle’s book. Our book then, After the Night basically has a structure, it’s sort of three parts. There’s one part which is kind of a straight rewrite of The Night where we inserted our own characters and put it in the present tense. And the second was a series of correspondence around the translation itself, which served as a second layer of narrative. And the third one was a visual essay, which was literally based on The Night and set in the south of France. So by the time we finished a book, I think we’re in 2013, and there’s no more Occupy. The book ended up being a lot about sort of the vagaries and futilities of translation itself, and sort of quite an inward-facing narrative. Not to say everything was doom and gloom, we did end up playing a lot of chess with Michèle, and eventually beating her a couple times. It was kind of fun. [09:32]

MOA – At the same time, and in the years following from that, a big part of our practice was also devoted to a magazine called Bon, which we art-directed and designed as well as co-edited. When we started working on it together, one of the first things that we did was a complete redesign of the magazine, which included everything from the size, the paper and the structure of the magazine, and to the typefaces that we used. Bon was an independently published fashion and culture magazine with a big emphasis on contemporary art. This feature from 2013 is with Carsten Höller, who was interviewed and photographed at his home in Stockholm. And the interviews that were published with artists were often followed by a curated portfolio of unpublished work by the artist. We approached all aspects of making this magazine in a collaborative way. We were treating all parts of the magazine as a testbed for collaboration and commissioning, and also for trying out new things for the design, which differed quite a lot from issue to issue. And we’ve always tried to be as mindful as possible of diversity, of course, in the choice of the people who were casted and photographed and interviewed for the magazine, but also in terms of contributors and who we collaborated with. [10:59]

ERIK – So the business model of most contemporary magazines is kind of predicated on the sales of selling ad pages. Often the magazine also exists to get more work for whoever produces it. So in the case of Bon, Bon was published by a creative studio called Studio Bon. Basically, within the context of mine and Moa’s works, we worked within an editorial team based in London. We had a lot of freedom producing the magazine, pretty much we could do whatever we wanted with it, as long as it was really good. And we didn’t work on the client projects really, with a couple of notable, quite disastrous exceptions. And so we had this practice where we worked editorially, as sort of cultural journalists, art directors, designers, editors in sort of context of the magazine, and we didn’t really work on client projects. And this felt good for our conscience because it felt like we weren’t really touching the advertising side of things. But ultimately, our work producing this award-winning magazine was a large part of the reason why the studio had advertising clients in the first place. And so even though we didn’t work in advertising, we didn’t want to work in advertising, we kind of indirectly did. And I suppose this created a fair amount of tension both between, not between, but like within ourselves, and eventually also with the publisher. And so in 2017, we stopped working with Bon. [12:31]

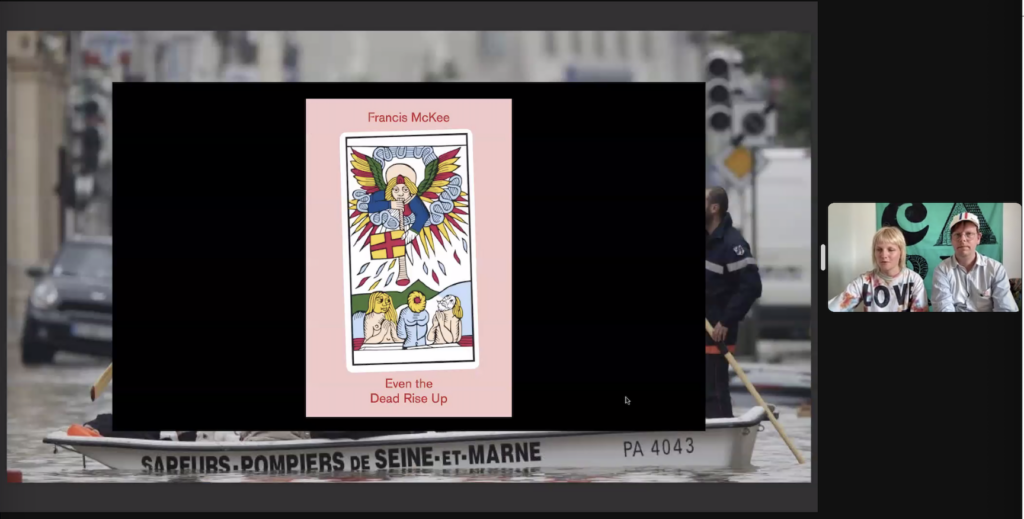

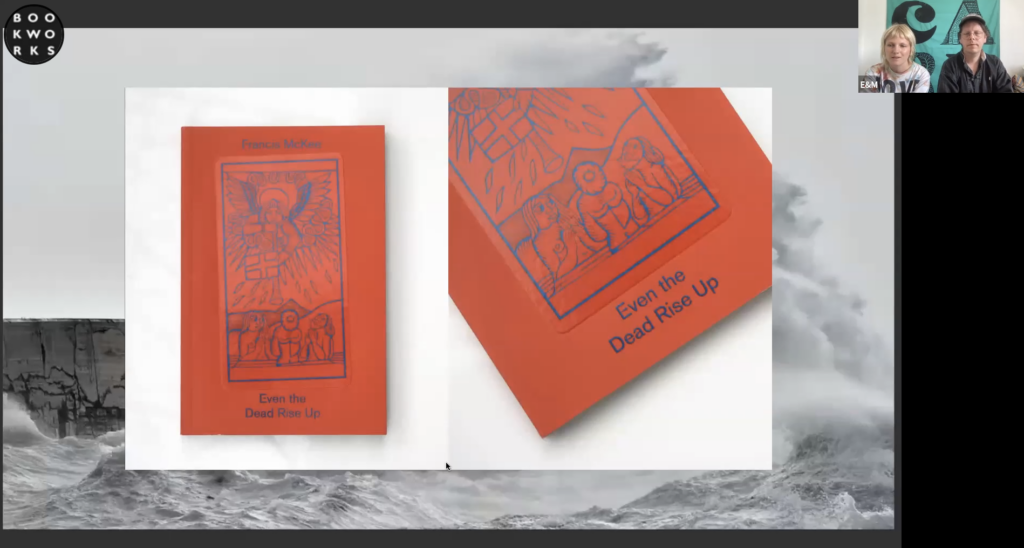

MOA – So going back in time, a little bit. In 2016, we were invited by Book Works, now as designers, to work with Francis McKee on his book, Even the Dead Rise Up. This is a quote from the book. To our first meeting, Francis bought a deck of tarot cards, which for us, as designers, were like super intriguing artefacts, and they also play a big part in the book. And the text itself is a very tender reflection on spiritualism, activism, life and death. And Francis also presented us to his extensive archive of protest photographs, which is an amazing body of work that he’s still updates today. The other day, I found some photos from COP 26, in Glasgow on there, which was great. And so when putting this talk together, it’s made us realise the importance of keeping notes on your design process, to like, write down what choice you make and why. And that’s a note to ourselves for the future. Luckily, we seem to never delete any emails, and this was definitely helpful for us to refresh our memories, when thinking about this project. This email contains a rationale for how we chose typefaces for this book, and I will now read a bit of this email.

So there is short and light-hearted rationale for choosing typography for this book, and it nicely sums up how we always tried to make choices about design and typography like, there should be a connection to the content, and it should be functional and these two should ideally be of equal importance. Plus, you get bonus points for a bit of humour. We originally suggested that this book would be a soft pink with a four colour printed tarot card, but it turned out Francis wasn’t into this colour at all. And here you can see the final outcome. So red instead of pink and with a two colour print with an embossed and varnished tarot card; and a two colour cover derived from an earlier idea that we had making the book a hardcover with a coloured cloth and a one colour print on top of that. We later dropped this idea of the hardcover as everyone agreed it was a too precious choice for the novel, but this process would definitely influence the final result. Oh yeah, and the pattern on the inside of the cover, as you can see teeny tiny bits of here. It comes from the reverse of the tarot cards. And we also used a selection from Francis’s photo archive for the start of each chapter. [16:06]

ERIK – So, Francis’ book was printed by Aldgate Press, which is a small cooperative concern, which started out as an anarchist press in the early 1980s and now operate out of a railway arch in Bow. So in this picture, you see Steve, who works there, and the upside down creature is our son, Morris. So we’ve been working with Aldgate for many years, and we try to do as many projects as we can with them. They’re very affordable, I would imagine, I suspect it is because they have quite low overheads. So they don’t have the latest fancy digital printing systems, their presses are quite old. And again, they’re located under a railway in Bow. And they’re also a cooperative, so everyone is paid the same. We love working with them. It’s very hands on, it’s almost like working with family. It’s useful for us because when we produce printed material, we always try to be mindful of helping produce things which are ultimately affordable, and accessible and with as sort of low environmental footprint as possible. And having a local partner really helps for them.

MOA – So between the years 2014 and 2019, we had a design practice running that we enjoyed, and that was in some ways pretty successful, at least from the perspective of the art school students that we had been a few years earlier. We had the privilege to work with clients in the cultural sector, both here in the UK and in Scandinavia. But clients we liked were universities, artists, small publishers and galleries. We were also able to keep our integrity as designers, and the negotiations were rarely too difficult. We also made enough money, just about, to have a life and a small family in East London. During this time, we also started teaching at the UAL [University of the Arts London], which is something that we still do to this day.

ERIK – Okay, so by now we’re sure you paid attention to the background images that we use throughout the talk. We mentioned in the beginning that this talk has three parts. And I’m about to begin part two, which is an excerpt from an Extinction Rebellion talk that we do to introduce people to civil disobedience and the climate crisis. So what I am going to read to you is just part of that talk, and I will keep it fairly short. The topic of this part is pretty heavy. So if you don’t want to hear it and need a break, just mute us for now or skip forward if you’re watching the recording. And when you see the slides changing again, we will have moved on to the third and final part of our talk. Before I begin, I’d ask you to just take a moment and visualise a person, a thing, or a place that you care about very deeply. You might want to get a pen and write down the name of this person, thing, or place on a piece of paper and place it in front of you. [19:20]

Okay, I’ll start. So, right now we’re experiencing the sixth mass extinction. Our life support systems are collapsing around us. Doubling down on fossil fuels is insanity and the politicians arguing for it now, they aren’t fit to lead us. The latest IPCC report from the world’s leading scientists came out two days before Ukraine was invaded, and so it was ignored. The UN Secretary General described it as an atlas of human suffering. He called it a “damning indictment of failed leadership.” Wildfires, floods and extreme weather events already seem normal to us. Even if we stopped all burning tomorrow, the ice will keep melting, deserts will expand, sea levels will rise and crops will fall. The release of large amounts of CO2 and other greenhouse gases caused a cycle of warming, once set in motion, it doesn’t just stop when we stop burning fossil fuels. This is a fairly scientifically straightforward fact. But it’s not at all the impression we get from politicians or the media when they talk of gradually phasing out fossil fuels. As if the temperature will gradually reduce as we do so. The Chatham House risk assessment of last September described the likelihood and impact of massive simultaneous crop failures over the coming decades as global population rises and with it the demand for food. The same report said that we have a less than 5% chance of keeping global warming below two degrees from pre-industrial levels. At two degrees of warming, the Met Office tells us we can expect to see ome billion people at risk of deadly heat stress. And it started already. There’s currently a heatwave in India and Pakistan, which is getting deadly. The average daytime temperature in July, in a small town called Lytton in Canada is 21 degrees, which is similar to the UK. Last July it was 49.5 degrees. The town was literally set on fire— you’ll remember the images. People can’t live, they certainly can’t work at 50 degrees. In the news a few weeks ago, we saw that Antarctica was 40 degrees hotter than it normally is for this time of year. And we haven’t even got to 1.5 degrees yet. And we know that the warmer it gets, the warmer it gets. We’re probably past several irreversible tipping points already. You can see the satellite images of the retreat of Arctic sea ice. This process has been set in motion and it won’t just stop. White ice reflects heat from the sun. So, when the white ice is gone, the dark blue ocean that replaces it absorbs the heat instead. Forests absorb carbon from the atmosphere, but now, as they are being cut down and burned, they are instead releasing it. There’s talk about planting more trees. But what’s actually happening is that an area of forest the size of London is lost every week. That’s roughly an area the size of the UK every year. It was around 1990 that the public and politicians became widely aware of how urgently we needed to reduce and stop fossil fuel emissions.

Since then, since the time we knew we had to stop, we all knew we had to stop, the total quantity of global emissions has more than doubled. Year after year, conference after conference, election after election, promise after promise, emissions continue to rise. And this is what scares me the most. It’s our capacity, human’s capacity to know what’s happening, and not only do nothing about it, but make the situation collectively worse. We continue to tell ourselves stories about the future, stories that we want to believe that make us feel better. We do our recycling, eat a bit less meat, might even become vegan. Think about switching to an electric car, maybe even write our MPs or sign a petition. And what happens? Well emissions keep rising. You can say it’s China’s fault. But the emissions come from China because we buy the stuff they make. It doesn’t matter where the emissions come from when your home is flooded, or you can’t buy food. The only thing that matters is what we do collectively.

This is why we need real democracy and real leadership. Most people know that things are bad, but basically assume governments are taking care of it. Unfortunately, the evidence is unavoidable. Governments just aren’t taking care of it. According to Oxfam, the richest 1% globally have been responsible for twice as much CO2 Over the last 25 years as the poorest 50%. So this is very much a crisis caused by the rich, and inflicted first and hardest on the poor. So, crisis driven by profit. Corporations are legally obliged to maximise their profits for shareholders, it’s just what they do. When what are considered environmental concerns clash with economic concerns, the money wins every time. It’s impossible to overstate how much the interest of bankers and big business influence our politicians’ decision making. When politicians say, “we can’t possibly do that.” What they mean is, “some rich people I know don’t want that to happen.” I’m almost at the end, but I’m going to read a quote from Martin Luther King, it’s pretty direct. Before I do, I’d like you to bring back again, to your mind that person, place or thing you thought of at the start, if you did write it down on a piece of paper, you might just keep it in front of you and keep it at the front of your mind. [24:36]

Quote: “If you’ve never found something so dear and so precious to you that you will die for it, then you aren’t fit to live. You may be 38 years old as I happen to be, and one day some great opportunity stands before you and calls upon you to stand up for some great principles and great issues and great causes. And you refuse to do it because you are afraid. You refuse to do it because you want to live longer. You are afraid that you will lose your job or you are afraid that you will be criticised, and so you refuse to take the stand. While you may go on and live until you’re 90, but you are just as dead at 38 as you will be at 90. You died when you refused to stand up for rights. You died when you refused to stand up for truth. You died when you refused to stand up for justice.” End quote.

Our only choice right now is to force the government to take responsibility. If you have any idea of how bad our future looks, then you only have two choices. You can lie to yourself, or you can take meaningful action. Sounds blunt, sounds kind of rude. I know that. A few years ago, I wouldn’t have been able to be in front of people and say it, wouldn’t have been able to read that quote from Martin Luther King and suggest that if you don’t do something, you are as good as dead. We don’t say it lightly. But it’s true. And this is foundational to everything that we do. The truth is often not what people want to hear, but we have to say it. [26:02]

Okay, so that was part two, and what I just read to you is part of the talk, developed by Extinction Rebellion in a working group that we’re in. The talk is longer, it has parts that can help you if you are feeling hopeless and helpless. The talk is called Look Up, Step Up. And you can attend a talk by checking out Extinction Rebellion events near you, either on Facebook, or on the XR website, or you can send us an email, we’ll put an address at the end of this talk. So, let’s get back to our talk again, which we are now giving a new title. So we’re two graphic designers with two kids and a mortgage, what the hell are we supposed to do about climate change?

MOA – Back to where we left off in 2018. In spite of having a practice that was pretty ethical in the sense that we didn’t work with huge corporations, etc. the state of the world was really creeping up on us. In October 2018, after that insanely hot summer, and about a week after the much publicised IPCC report came out, we had our second child. And we think, and we hope that it’s pretty clear by now that having a sustainable practice has always been important to us. And that we were by no means ignorant about the state of the world and the multiple crises going on. But this was new and the combination of having a new baby and the fact that climate change for once was front page news, that had a very, very big effect on us. So, in the spring of 2019, we sort of reached the point where we felt like we had to make some big changes in our way of working, and in our way of living. What we previously had done, like being vegetarian, we were buying bamboo toothbrushes, and we’re trying to print and produce our projects as sustainable as possible. That wasn’t enough anymore to keep the anxiety and the fear at bay. [28:03]

ERIK – So this banner, which was hung on Westminster Bridge, by Extinction Rebellion in November 2018 really summed up our feelings well, and we learned more about Extinction Rebellion. XR used nonviolent tactics, and they were disruptive and annoying and loud, but they also seemed to have a very clear strategy, and they felt like they really knew what they were doing. They would target cultural institutions, some of which we had previously worked with, such as London Fashion Week here. They also had arrived with a large degree of humour, and an emphasis on design and language, and also clear targets in the form of instruments of power. So governments and media, and lately also finance and oil companies. They were definitely putting words to our feelings. And beyond that, they had a great knack for creating situations in the situationist sense of the word, that I brought up in the beginning of this talk.

MOA – In the early summer of 2019, a couple of months after this pink boat descended at Oxford Circus, we joined Extinction Rebellion, or XR as we often call it. At first we joined our local group here in Tower Hamlets where we lived, and we started going to actions. Which was at least for me, a completely new thing, as I had never been an activist before and I could, like count the number of protests that I had ever been to on my two hands. We also got involved in the local art group. Most local groups will have an art department, and we were making some designs, and we did some screen printing for the group like these flags we did for the summer uprising in the summer of 2019. And yeah, pretty soon after that really we got involved in XR’s national design and art group. We sent an email saying, “Hey, we’re two designers, we have some hours a week that we can spare to help the movement with our skills.” And these few hours per week soon became most hours of the week. And since the beginning of 2020, we have been involved more or less in a full time capacity. So we now co-coordinate the design group of XR UK. And we are now going to show you some of our outputs, and it’s very important to say that all this work is the fruit of a very deeply collaborative process, which involves a lot of people that aren’t us; from writers and thinkers, to engineers, to printmakers and nurses. And like all the brilliant and brave activists that we work with every day. We will also be focusing on our work as designers as this is meant to be a talk about design, but we also want to say that we do engage with the protest side of things as XR. After all it is a movement whose main tactic is civil disobedience and not graphic design. So what has changed in terms of our practice then? The short answer to this, nearly everything. We now design fewer things for artists with a formal training, and more things for people who are prepared to be put in handcuffs and carried off by the police. Another big change is the scale of things. So the size of the objects that we design now is often much bigger; such as banners that are used to decorate statues, or block roads, or canopies for large bamboo structures also used to disrupt; or vans going on mobilising tours around the UK. Another big change is that we do see our work in the media much more frequently than before, or in social media. And many of the things that we do design these days are in fact designed to end up in the media as part of actions that are designed to draw attention, and thus be photographed. But that’s not everything. We also design a lot of outreach materials such as flyers, leaflets, and posters. Some of these posters are printed commercially, but a lot of them are handmade with messages and images that are produced in collaboration with other activists and other designers and artists. As a graphic designer, there’s something really, really enjoyable we think about making posters; it is like visual communication in its purest form. It’s something that you learn when you go to art school, and it’s something that we teach our students, but we never really designed or produced many posters as part of our professional practice before we joined XR. But in the activist space, there’s a huge demand for posters and we’ve made and designed more posters in a couple of years than in all the other years of our practice combined. [33:23]

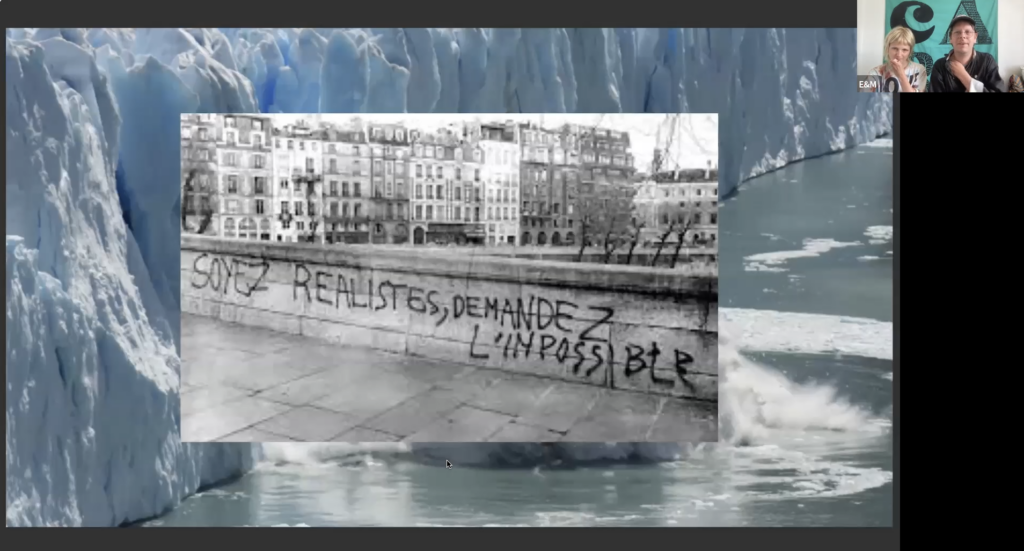

ERIK – And the act of putting the posters up as well, is a form of civil disobedience. I mean, we often call it a joke crime, but it is still illegal. In XR going out fly posting is often a gateway drug….gateway drug?! Gateway action, for new joiners to the movements, and posters are also a brilliant canvas for exploring humour and language. So one of the things, as we became more integrated with the XR art group, we learned that we share more than a few heroes with them, not least the Situationists again, which we started this talk introducing. So the key message of XR is “demand the impossible”. And that itself, is stolen from this famous graffiti from Paris in May ’68. I’m going to quote Michèle Bernstein again. She wrote in the preface to a reedition of a French photography book that has pictures of graffitis from the famous occupations quote, “What did the walls want? To see life with new eyes. There was a rejection of the consumer society. There was freedom, there was love.” Quote, “I came on the paving stones.” End quote. “Irony, without which the human being is not a thinking creature, and especially utopia. Be realistic, demand the impossible. We know that utopias leave indelible traces.” So, here’s the english translation of the graffiti you just saw in some XR graphics. The language of XR owes a great debt to situationists including our dear Michèle. XR even has its own screen printing and poster making outfit. It’s called Paris 68 Redux, in honour of the Atelier Populaire, who produced many of the memorable posters back in 1968; and they’ve developed methods and techniques for mass producing posters together by hand. [35:19]

MOA – Back now two bigger things, again, such as banners. And actually, to design a banner isn’t that different from designing a book cover, at least in some ways. They are both meant to catch the eye of the audience and communicate the essence of the content. So the text or the reason for the protest in an immediate way. So, when we design a book cover, we design it to exist in the context of other books, such as in a bookshop, or in a publisher’s catalogue, and also for the audience that is likely to engage with that book. If it’s, for example, an artist’s book, it is reasonable to make certain assumptions about who that audience is in terms of their interest in contemporary art and design, and their degree of education etc. So that audience is likely to be fairly sympathetic to the work, or at least not likely to judge it negatively, just on the basis of the cover. With the banner on the other hand, you can’t make assumptions about the audience in the same way. You can be pretty sure that a large part of the audience won’t be sympathetic to your banner, or the content, i.e. the protest or the tactics used. So nuance is difficult, and it often pays to be direct, and it often pays to be provocative. Being judged for your banner is inevitable. But even if the reaction from the audience is negative, to make people react and stop and think, is useful.

ERIK – Another thing to keep in mind is that banners and placards are most often held by people. And those people themselves are most often not part of the design process. And so there’s this constant negotiation to be had with the people in the movement to make sure that we’re designing and producing things that people agree with and want to stand behind. In the case of XR, this is kind of both difficult and easy at the same time. It’s easy, because as a movement, we all align on the need for action on climate change. In the knowledge and acknowledgement, of course, that the climate crisis and ecological crisis are both a cause and effect of other crises, such as capitalism, or racism, or patriarchy or colonialism. And the difficult part is that within the spectrum of other crises, it is not always useful to bring specifics to the forefront. So XR as an organisation is global, of course, and it contains a mass of people who all agree on the need for climate action. But they might disagree or have no answers on the other part. So yes, we care about Palestine, and at least we would attend demos protesting the treatment of Palestinians by the State of Israel. We care about trans rights, same, we care about debt relief and reparations for Africa, we recognise that these issues are connected with the issue of climate. But putting these specifics on banners and placards is most often not going to help you keep a unified strong voice as a movement. So you need a different language, you need a language that can hold all of this without necessarily being explicit. So in XR, we often use words like care and empathy and freedom, grief, we speak of death. These things, this language helps ground our actions and bring people together rather than divide us.

The other thing we want to keep in mind is that the nuances and personal motivations of activists themselves, they are of course, of paramount importance. If we can design things that enable them, encourage them and put them at the forefront so that their motivations and their thoughts and their language can come through interviews, or through megaphones, or through discussions with people on the streets. In short, people using their own voice to share their own reasons for why they’re there. Then we’ve sort of done our job. So as designers, we always try to— our focus is to try and help create scenes and interventions or situations -in the situationist sense of the word- that are visually impactful. But that also focuses attention on the people taking part, and through that we can help enable and encourage individual voices to be heard. Another way in which the design process and XR is designed to be inclusive, is that one of the main ethos of the XR group is that we do things together. So this picture is from one of the XR art factories, which is warehouses, or the specific warehouse is set up where everything from banners to props for protests are created by volunteers together. This has been decentralised all over the country in the UK, there are a series of these warehouses where we make things together as a movement. Even our design programme, so the thing that sort of counts as the visual identity of XR, is open source for anyone who works to actively change the world for the better. And we do share it with anyone who asks.

MOA – The banner again. This is a favourite banner that is out for a walk outside 10 Downing Street in September 2020. Before we joined XR, we were used to working with clients who were well educated in terms of design and communication. And as we mentioned previously, the negotiations that we had with them were usually intellectually stimulating and rarely very frustrating. Working within XR is very different, we do need to constantly balance the need to have a coherent voice and strategy, with a need to accommodate the wishes of a decentralised movement of tens of thousands of people, not to mention the public whose degree of support fluctuates. This is challenging to say the least. We constantly need to remind ourselves that we cannot please everyone, as you then often end up pleasing no one. At the end of the day where we are doing the work to effect change, and not necessarily always to be liked.

So what does it mean to have a design practice in the face of an emergency and to take this statement seriously? We still live in London, because it would be much harder for us to do the work that we are doing if we were somewhere else. We do have our London bills to pay, and we do have our London childcare costs to pay, and we have London pint costs to pay. We are now even more selective with the work that we do take on. So to do what we did earlier, to maybe once in a while accept a project for a large client in order to survive on the work that gave us the intellectual stimulation and prestige. That just isn’t an option anymore. But luckily, the shift in the way that we live our lives now, meaning less travelled and less consumption etc. does help to balance it out a bit. We do also receive a bit of money from XR which helps with childcare costs. Of course, also the shift in our context and where we work, like going from one bubble to another bubble, has also brought some new clients who we are very proud to work with. And we do still have clients in the culture sector, even they are fewer now. It’s important to say that whilst we don’t believe that making individual lifestyle changes will save the future of the planet, or the future of humanity, for that matter. For us, making those changes to our everyday financial choices has meant that we can afford to be activists. It is a privilege, and we are very lucky that we’re able to do this. [43:20]

ERIK – So yeah, as Moa just said like it’s been…we are lucky. Like we are very privileged that we can do this. We also do it because the work we do with XR, we do it because we really believe that civil disobedience is our only chance. Because governments are just not going to save us. I mean the work we do for XR, we do it because we believe it is useful, that even effective activism, which ultimately is about civil disobedience and not pretty graphics, culture is important. Design is important and images matter. That’s also why we are doing this talk. We sacrificed a large part of our practice to be able to do this. Like I said, we also gain loads. But that’s us. So our question now is where is everyone else? So there are artists and writers and curators that are engaging with the climate and ecological emergencies, but there’s not enough of us. So our feeling is that we all need to step up. We need more people. We need all people to engage in protests and civil resistance against our governments. But we also need everyone to engage with it within their practice, to talk about it, to engage with it, to write about it, make films, art, books about it, to curate shows about it. Frankly, it should be all that we do. It should be all that we talk about and work with. So, we’re going to leave this with an invitation to join us. You can join us in XR if you’d like to everyone is needed and welcome. If that’s not your bag, go do something else! Use your skills and your network and your platform to effect change. Moa spoke about bubbles and we don’t meet enough people from our former bubble which is in this space, inside our new bubble. And we really hope that through this talk we have shown that it is possible to have a creative practice and thrive and still take a stand for life and have some fun doing it often. So please get in touch either to just connect with XR, or have a conversation about protest and activism, or the role that art and design and culture will have within that.

MOA – Or come and do some design for XR.

ERIK – Because lest you forget, the same government that is currently busy destroying our chances for climate action. They’re also after the arts. So this is from May 16, an article that is telling us that Jacob Rees-Mogg is after the Arts Council.

MOA – On this bleak note, we can say thank you very much for listening and do get in touch and have a great day. Bye.

ERIK – Bye. [46:05]

Their new studio, Not Here To Be Liked, has now been launched. Information and resources mentioned in the talk can be found here: Extinction Rebellion